CONTENTS

1.

TRANSITIONS

2.

The ROLE OF DDR IN TRANSITIONS

3.

FROM THE UN TRANSITIONS PROJECT

4.

Field CONTEXTS: DRC, HAITI, MALI, SUDAN

5.

KEY LESSONS

6.

ON THE FIELD: MUNIGI CAMP

7.

Recent publications

8.

Upcoming events and trainings

1.TRANSITIONS

The withdrawal or drawdown of a UN Peacekeeping Operation or a Special Political Mission represents a critical transition for a host country and the UN configuration and presence. On one hand, it signals progress towards peace and new opportunities to further consolidate development gains, but at the same time presents risks that need to be addressed through sustained investment in peacebuilding and longer-term efforts to overcome fragility so as to not lose such hard earned progress. The UN’s legacy in a country emerging from conflict depends largely on how it has supported national actors and coordinated with international and regional partners to consolidate the political and social gains made during the mission’s presence.

If well-planned and well-managed, transition processes can increase the prospect of sustained peace and durable development. If ill-timed or mis-managed, such transitions can pose a challenge to previous peacebuilding efforts and may result in a relapse into conflict and protracted crises. While the UN has undertaken several transitions, withdrawals, and reconfigurations over several decades, the need for effective UN transition planning has gained considerable momentum and attention over the last 12 months, with the governments of DRC, Mali and Sudan initiating transition processes and with early transition mechanisms taking place in several mission settings, including Central African Republic (CAR), Haiti, Somalia and South Sudan.

Across these handful of transition settings, many lessons can be drawn. What is the right sequence of activities for an effective drawdown? How does the Mission prioritize mandated activities as it scales down its activities both geographically and thematically? And how do Missions communicate this strategically and keep populations informed in the wake of disinformation and misinformation? How can we assess the effectiveness and even success of a transition? Do hasty withdrawals undermine the gains made during the timeframe of the UN’s presence? What are the significant challenges that departing missions face in ensuring business continuity with broader UN efforts in the development and humanitarian sphere?

This edition of the DDR Bulletin seeks to delve into these questions, as well as highlight common challenges and lessons learned from national institutions, DDR and Community Violence Reduction (CVR) practitioners in field missions, partner organizations and UN colleagues who have worked within transition settings in a variety of contexts. In this regard, this Bulletin primarily focuses on the process of transitions through a Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) lens, considering how these may impact DDR efforts and legacy, reflecting on the contexts of DRC, Haiti, Mali, and Sudan.

In order to ensure the broad scope of the Bulletin, the DDR Section has conducted over 20 interviews with a variety of different interlocutors serving different tasks and positions, from national staff to the heads of UN missions and representatives from key political partner institutions.

“Exploring how DDR/CVR can effectively support transitions and prevent conflict recurrence is crucial”

2.THE ROLE OF DDR IN TRANSITIONS

The UN integrated DDR (Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration) process holds paramount relevance in the broader context of transitions, particularly during post-conflict periods. DDR serves as a crucial component in transitioning from conflict to sustainable peace and development. DDR contributes to the reduction of security threats and the prevention of the resurgence of violence, whilst primarily aiming to reintegrate former combatants into society, fostering social cohesion, stability, capacity development towards a sustained peace approach. DDR programs aims to address the root causes of conflict, promoting reconciliation, and supporting the establishment of effective governance structures. In the context of UN transitions, DDR initiatives become instrumental in consolidating peacebuilding gains, bridging critical capacity gaps, and ensuring that the withdrawal of a UN mission leaves a positive and lasting impact on the political, social, and economic landscape of the transitioning country. The UN’s commitment to DDR underscores the recognition of the intricate link between disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration and the overarching goal of sustained peace and development in post-conflict environments.

Transitions are important moments in the “peace continuum” of a country emerging from conflict. As such, ensuring pro-active, integrated, and forward-looking transition planning and management is a key priority. As transitions are highly complex and multi-faceted in nature, all posing their own unique set of challenges and dynamics, this Bulletin delves into the different perspectives of a variety of different stakeholders and actors, from DDR/CVR practitioners to national authorities, representatives from political institutions, UN colleagues and partnering organizations.

Arthur Boutellis

Non-resident senior adviser at the International Peace Institute (IPI)

“The context of transitions is important when considering lessons learnt”

Khaled Ibrahim

Principal Coordination Officer, Political Affairs, MONUSCO

“Political engagement, joint analysis and capacity building support… vital for a smooth transition”

Thomas Kontogeorgos

Chief Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) Section

“One of the key lessons is that transitions needs to be discussed, negotiated, and agreed with national institutions…it is important to be open and transparent”

3.FROM THE UN TRANSITIONS PROJECT

The UN Transitions Project represents the UN’s key mechanism to advance the system-wide work on more proactive, integrated, and forward-looking transitions in the context of mission drawdown and withdrawal. The UN Transitions Project is comprised of the Development Coordination Office (DCO), Department of Peace Operations (DPO), Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Initiated in 2014, the Project works to ensure that UN transitions result in a better positioning of the UN and its partners to support host countries move from conflict to sustainable peace and development. The Project provides country support, identifies, and shares lessons and good practices, and strengthens operational and policy coherence on transitions-related issues.

Meet the UN Transitions Project

Marlien Schlaphoff

Associate Political Affairs Officer in the UN Transitions Project Secretariat

Aryana Urbani

Policy Officer in the UN Transitions Project, supporting UN Peacekeeping Operations, Special Political Missions and Resident Coordinator’s Offices on transition planning and management.

Lorraine Reuter

Regional Transition Specialist

Jascha Scheele

Project Manager of the UN Transitions Project

In Conversation with the UN Transitions Project

How have transitions evolved?

In the past, UN transitions used to take place in environments marked by relative stability and peaceful handovers of power (e.g., Liberia, Mission closure in 2018; Sierra Leone, Mission closure in 2014; and Côte d’Ivoire, Mission closure in 2017). Today, the global context has profoundly changed and ongoing (e.g., DRC, Mali) and accelerating transition processes (e.g. CAR, Somalia, Sudan, and South Sudan) are unfolding in more complex settings, where security challenges and protection gaps persist, and root causes of conflict have not been fully addressed.

The UN’s approach to planning and managing transitions has evolved considerably over the last decade: from viewing transitions as a ‘hand-over of residual activities’ towards a forward-looking approach that aims to support national stakeholders and key partners towards successfully consolidating peacebuilding gains.

What policy and guidance is there available in managing UN Transitions?

The commitment to better plan and manage transitions is at the core of the Secretary-General’s reforms of the peace & security and development pillars; it has been mainstreamed into the Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) Initiative and the Sustaining Peace agenda, and implementation of the findings of the UN Integration Review account for early transition planning. In particular, the SGs Planning Directive for the development of consistent and coherent UN Transition processes, issued in February 2019, continues to guide UN Missions, Country Teams, and HQ entities, particularly on early integrated planning and financing, operational support, and staffing. Building on existing policy and guidance on UN integration, it provides a framework to advance both a development and a peace and security approach in the context of UN transitions, to sustain peace and development gains, reduce the risk of relapse into conflict, and help set countries on a path towards achieving sustainable development. In addition, with the adoption in late 2021 of the first- ever Security Council Resolution (SCR) on transitions, UN SCR 2594, Member States have expressed their commitment to further developing how the UN system prepares for transitions. This has been reflected in the SG’s Report on Transitions in Peace Operations of 2022 that provided an organization-wide analysis of the most pressing transition-related challenges that need to be tackled in the coming years and going forward charts a roadmap for collective action.

Building partnerships and making transitions less UN-centric

Experience from past transitions has shown that partnerships – with the host country, with bilateral and multilateral partners, regional organizations and International Financial Institutions – are of utmost importance for a successful and sustainable transition from a UN mission to the Country Team. The Transitions Project therefore closely cooperates with a plethora of partners, including Member States, the European Union, the World Bank, academia, research institutes, and others to ensure that the reconfiguration of the UN presence is a joint endeavor that leverages existing resources and creates a momentum for future engagement. A good example of this cooperation is the joint UN-EU workshop on transition partnerships that recently took place in the Democratic Republic of Congo and focused on strengthening cooperation in areas such as DDR, SRR and Protection of Civilians putting particular emphasis on aligning existing activities and creating mechanisms that allow for a close cooperation and coordination between the UN and its partners.

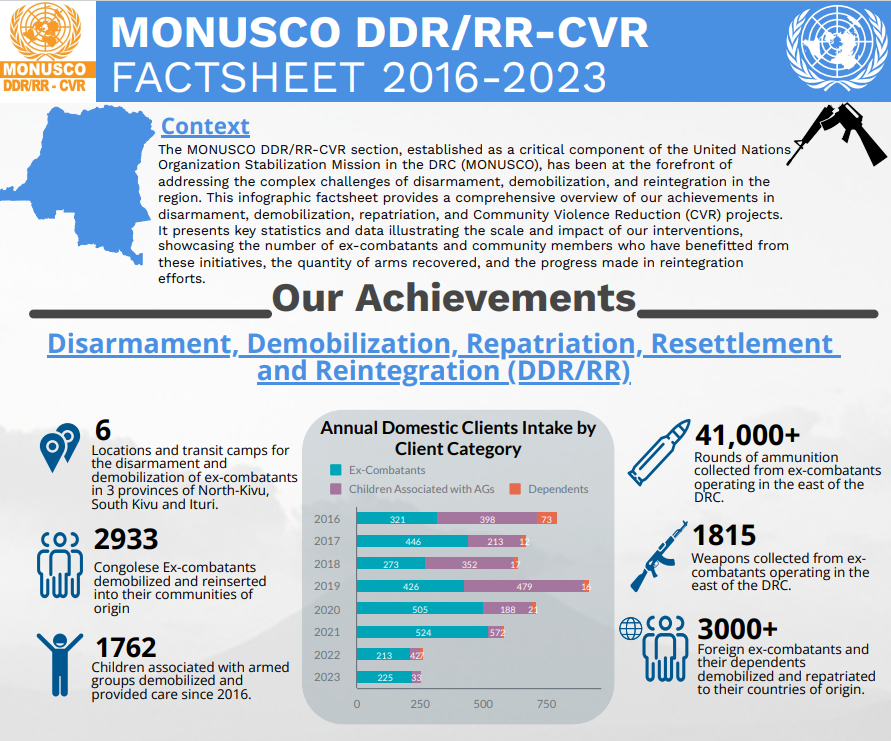

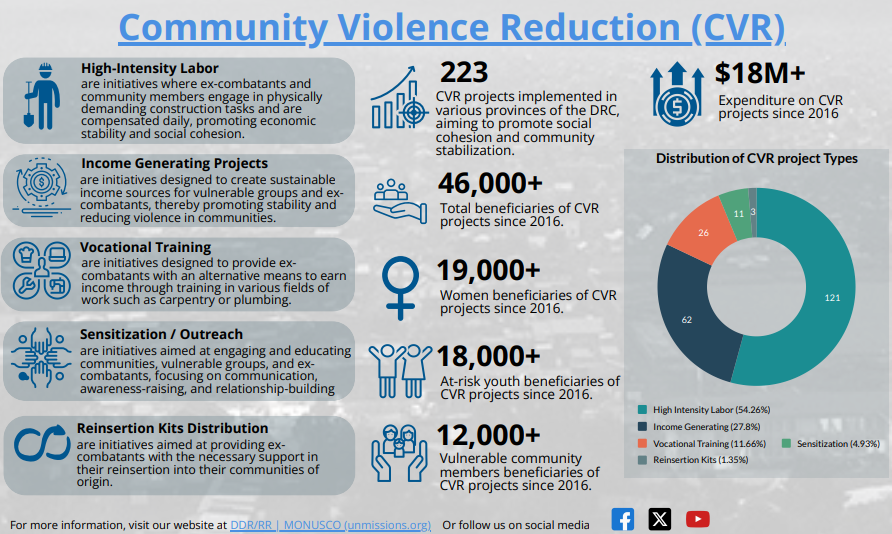

ON THE FIELD: DRC

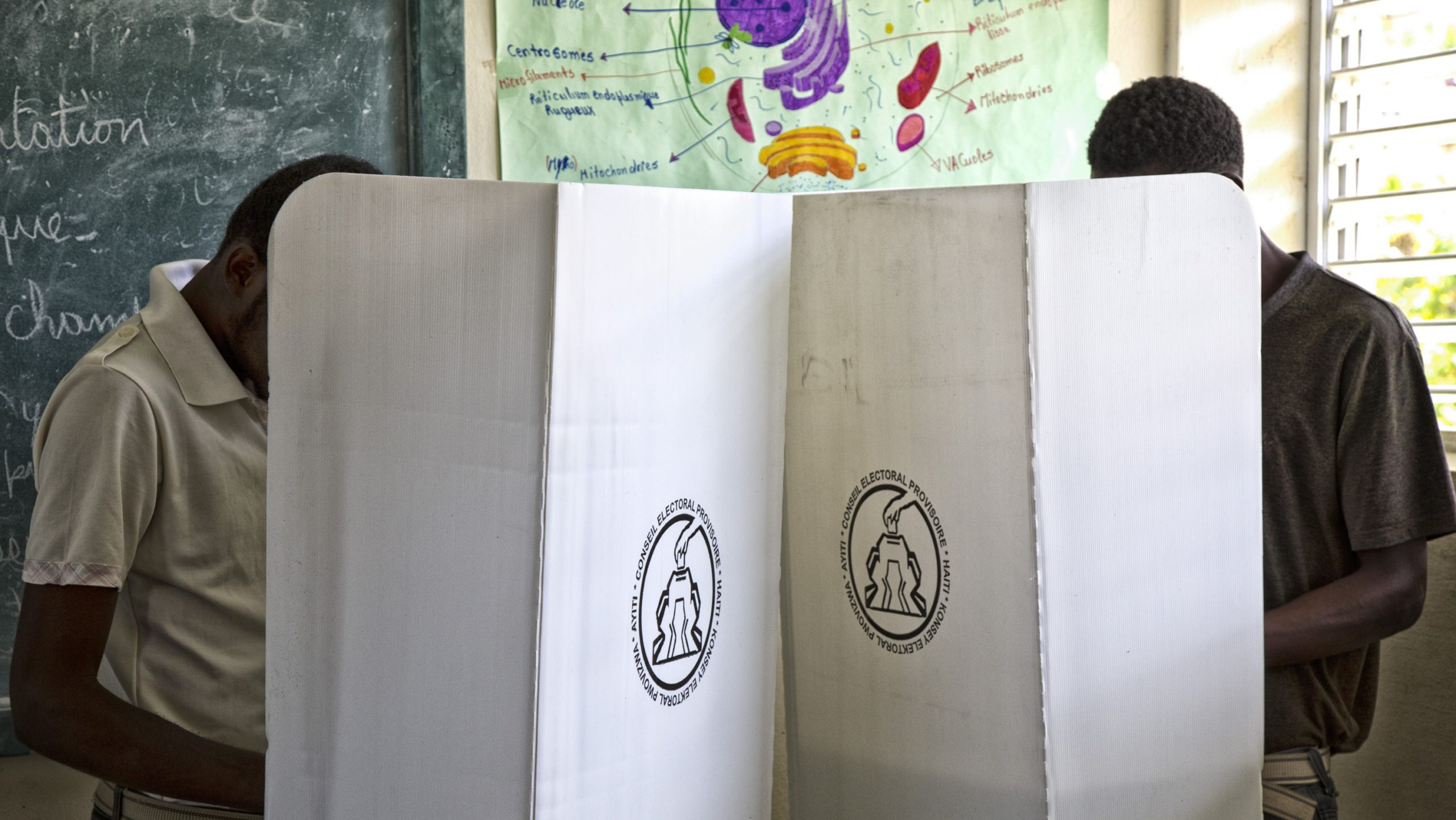

The UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) is also undergoing a transition, with the Congolese government calling for its accelerated drawdown to begin by the end of 2023. The DRC, with its history of conflict and complexity, presents lessons for the UN in managing transitions. The UN Security Council renewed MONUSCO’s mandate on December 19, 2023. The Security Council on September 1, 2023, called for the mission’s accelerated withdrawal to commence at the end of 2023, the government and the mission’s signing in November of a disengagement plan to implement this accelerated withdrawal, and the general elections slated for December 20, 2023. The past two months have seen renewed fighting between the Armed Forces of the DRC (FARDC), the M23 rebel group, and other armed groups. The Nairobi and Luanda peace processes were disrupted by the resumption of hostilities and heightened tension between the DRC and Rwanda. The security and humanitarian conditions continue to worsen in the eastern provinces of the DRC, with persistent threats to human rights and the protection of civilians.

The UN’s role in the DRC underscores the need for adaptable strategies that consider the fragmentation of armed groups, political instability, and resource constraints. The transition in the DRC reinforces the idea that successful DDR requires not only disarmament and demobilization but also comprehensive approaches addressing the root causes of conflict. Lessons learned stress the importance of sustained engagement, sufficient resources, and collaboration with local authorities and international partners for a successful transition.

Khaled Ibrahim

“Political elections constitute an in very important milestone in the transition process in DRC”

Khaled has been leading many multidisciplinary teams in several United Nations Multidimensional and Integrated Peacekeeping Operations in the field of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration DDR, Community Violence Reduction (CVR) as well as the nexus DDR-SSR (Security Sector Reform) in complex conflict and post-war settings.

An interview with Daniel Maier

Daniel Maier

Senior Mission Planning Officer, MONUSCO

“For a successful strategy… the national DDR strategy is pivotal for a successful exit strategy, as it is closely linked to mandated priorities, such as Security Sector Reform (SSR) and the gradual and responsible transfer of protection of civilians responsibilities to the national authorities”.

From a strategic planning perspective, what insights can you share with DDR colleagues and senior management working on transitions, particularly in terms of processes, which have proved valuable in supporting transition efforts?

Daniel Maier: MONUSCO’s transition has been an ongoing process for several years with a focus on concentrating the mission’s footprint in areas where the risks for civilians are still very high. This explains why a geographic approach towards transition was chosen which led to the closing of several field offices in areas of the DRC where the security situation had improved over time.

As far as the DDR process is concerned, we advocated for a strong coordination between political initiatives, including at the regional and provincial level. For instance, the Nairobi conclaves brought together representatives from affected communities and armed groups with a view to determine how communities at risk could benefit from demobilization and disarmament, as well as the reintegration.

Lessons from past processes helped to achieve an understanding of key principles for a successful strategy and led to a shifting of its focus towards “community stabilization”. By the time the first comprehensive transition plan was adopted, back in 2021, the promulgation of the ordonnance for the national strategy for the implementation of the Demobilization, Disarmament, Community Recovery and Stabilization Program (P-DDRCS) for ex-combatants came timely and was included in the transition plan as core benchmark.

What specific lessons are important in transition settings when it comes to DDR, financing, programmatic funding, and the sustainability of UN Missions’ mandated tasks?

Daniel Maier: In the context of the DRC several national programmes in the past did not yield the expected results. In my view this was linked to the absence of a political process that would actively engage regional actors. In terms of financing, it is important for the United Nations to bring together national and international partners to ensure that funding issues are addressed on the basis of a clear understanding of respective responsibilities. The collaboration with a national coordinator for the regional political process as well as a national coordinator for the national process helped to maintain the exchange of information and allowed stakeholders to participate in the design of programmes and monitoring of progress. The task is far from being accomplished but this approach clearly shows that DDR processes are multi-dimensional and cross-cutting. Whilst being a core benchmark for the transition various socio-economic dimensions of DDR must be incorporated in the ongoing Common Country Assessment and the forthcoming UNSDCF 2025, an important opportunity to anchor DDR in the UNCT programming cycles.

When would you suggest a UN exit strategy is considered successful?

Daniel Maier: Ownership is a critical element as well as flexibility. In the case of MONUSCO’s exit strategy we saw a wide spectrum over time ranging from “transfer of tasks” 2013 onwards to the “joint strategy on the progressive and phased drawdown of MONUSCO” in 2020 with a strong geographical focus. This focus has been reflected in the 2021 transition plan with 18 benchmarks and is still reflected in the disengagement plan that the Government requested in September 2023, and which was jointly developed with and co-signed by MONUSCO. The evolution of transition concepts reflects an evolving vision linked to the politico-security context both at national and regional levels. The Security Council, however, made it clear in its resolutions and quarterly hearings: the end state remains critical, and the protection of civilians must be at the center of all efforts. In this regard it is welcome that the Government is ready to step up its commitments to increase national capacities. For a successful strategy this also means that the national DDR strategy is pivotal for a successful exit strategy as it is closely linked to mandated priorities such as security sector reform and the gradual and responsible transfer of protection of civilians responsibilities to the national authorities.

Which would you consider essential ingredients for a sustainable transition?

Daniel Maier: Transition processes require time and the ability to accept setbacks. The importance of DDR processes in the DRC has been emphasized for as long as an international peacekeeping operation has been deployed. Community Violence Reduction initiatives remain an important element. However, those who managed to make a living as members of an armed group or local defense militia group need to be convinced that laying down their arms pays out for them and their families as with peace and stability many new opportunities will become available. International partners can only accompany such processes and help to create conducive conditions. The importance for sustainable transition therefore is to work with all actors to achieve localized “peace dividends”. This of course touches upon many aspects of governance, institutional reforms, and the gradual increase of national capacities through revenues that increase the national budget. In the context of the DRC this requires an understanding of conflict drivers and implies that the political economy of armed groups need to be addressed, and beyond national borders. Further regional integration could be therefore an essential ingredient to address foreign armed groups, as well as provincial peace initiatives that address the root causes of conflict.

ON THE FIELD: HAITI

Peacekeepers from the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) are in the final processes of leaving Mali under difficult circumstances following the ending of the mission’s mandate in June 2023 and withdrawal from the country by end of 2023. The UN’s engagement in Mali underscores the complex nature of transitions in conflict-affected regions. The situation in Mali has been marked by multifaceted challenges, including insurgency and political instability. Lessons learned from the Mali transition emphasize the importance of comprehensive approaches that address not only security concerns but also the underlying socio-economic factors contributing to conflict. The need for effective coordination with regional partners and local stakeholders remains critical for sustainable peacebuilding.

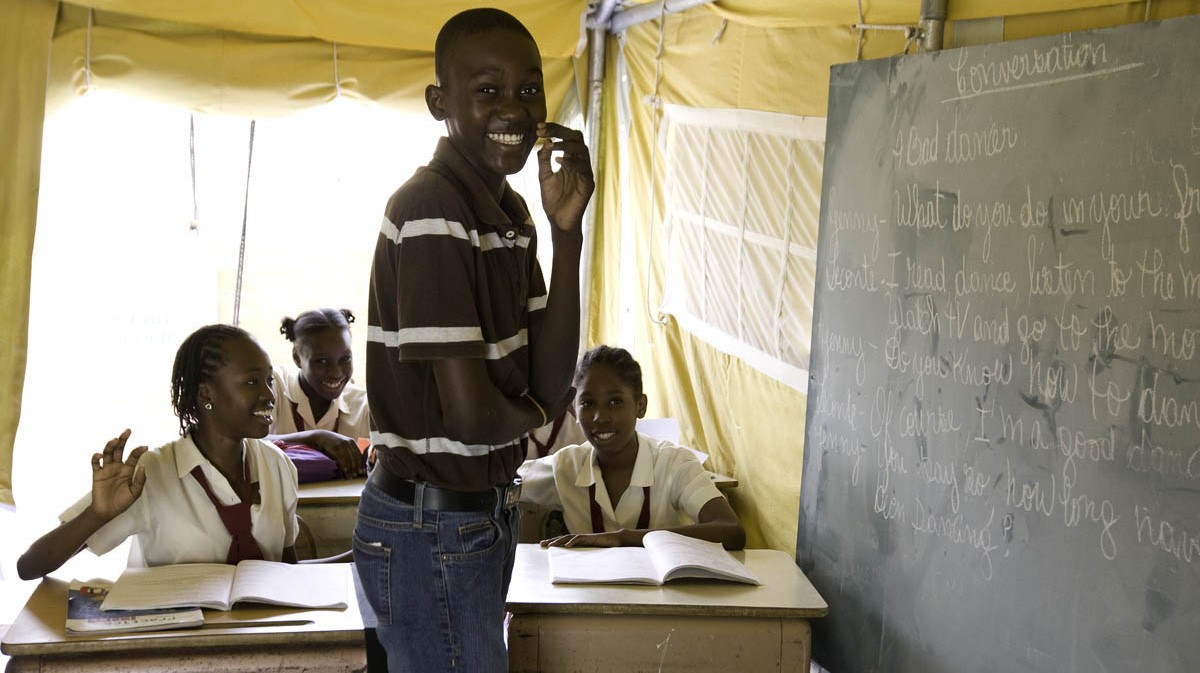

Haiti’s ongoing challenges have placed a spotlight on the complexities of transitions in fragile states. The UN’s engagement in Haiti emphasizes the importance of long-term commitment and resilience in the face of persistent socio-economic and political difficulties. Lessons learned from Haiti highlight the need for integrated approaches that prioritize both immediate stability and enduring development. Effective communication and coordination with local communities are crucial elements in navigating the intricacies of a successful transition.

Considering that Transitions are a complex and multifaceted in nature, it is highly important to consider the perspectives of all those involved. Click on the following buttons to find interviews of various different stakeholders and their perspective on transition processes in Haiti:

Luc Eucher Joseph

Primature

Pierre Emmanuel Ubalijoro

Governance and Community Stabilization Section (GCSS)

Monrose Jean Marie

Institute of Technical and Vocational Education (INFP)

Kettly Julien

NGO Institut Mobile d’Education Démocratique (IMED

Colonel Florexil Edwin

National Coordinator of The National Commission for Disarmament, Dismantling and Reintegration (CNDDR)

Joseph Foerster

DDR/CVR specalist

Antonio Gonzalez

Head of Mission, Viva Rio

Pedro Braum

Program coordinator, Viva Rio

ON THE FIELD: MALI

The UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) has formally closed on 31 December 2023 under difficult circumstances following the ending of its mandate in June 2023. The UN’s engagement in Mali underscores the complex nature of transitions in conflict-affected regions. The situation in Mali has been marked by multifaceted challenges, including insurgency and political instability. The recent MINUSMA’s withdrawal from Mali suggests that emphasis should be placed on the importance of comprehensive approaches that address not only security concerns but also the underlying socio-economic factors contributing to conflict. The need for effective coordination with regional partners and local stakeholders remains critical for sustainable peacebuilding.

Marie Chantal Lumba Tshimanga, DDR Officer with MINUSMA

DDR Officer in Gao with MINUSMA (2021-2023)

Marie Chantal is from the Democratic Republic of Congo. She has professional experience of more than 15 years in United Nations peacekeeping missions (in Mali, the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo), with the African Union and with international and local NGOs. .

In this interview, she shares her experiences as a DDR Officer in Gao with MINUSMA (2021-2023)

An interview with Marie Chantal Lumba Tshimanga

Based on your overall experiences with the UN, what insights can you share for the colleagues working on transitions, particularly in terms of processes, which have proven valuable in supporting sustainable efforts?

The transition concerns the period between the signing of the peace agreement and the effective and comprehensive implementation of the DDR process. DDR depends greatly on the political and security situation, operations remain technical and require good coordination and the involvement of all stakeholders in the process. Despite the challenges to overcome in supporting the DDR process in Gao, as DDR officer, the section supported and coordinated:

- Identification and implementation of MINUSMA financed projects to reduce community violence (From 2014 to 2023 more than 50 CVR projects were implemented in Gao region);

- Support for Accelerated DDR and integration operations into the regular army through the Operational Coordination Mechanism (MOC);

- Support for the socio-economic reintegration program for women associated with armed groups. In the Gao region, this process enabled the biometric registration of 206 women associated with armed groups from both signatory and non-signatory armed movements who benefited from a World Bank supported socio-economic reintegration program. MINUSMA provided a reintegration kit and a safety net to each beneficiary.

Drawing from your personal experience in Mali, what are the main challenges that come to mind when reflecting on key transition moments?

Challenge 1: The constantly changing context in which DDR was taking place in Mali is the main challenge. These initiatives were being implemented while clashes between the national army and armed groups went on.

Who will lay down their arms first if each armed group rival fears revenge attacks against them and the communities they claim to protect? At the same time, after laying down their arms, who will be able to protect communities? And how can civilians be sure that returning ex-combatants are not acting on past grudges?

Challenge 2: Unclear/or adaptable expectations of the armed groups signing the peace agreements. Like any other intervention in a sector as sensitive as security, DDR is shaped, facilitated and limited by the context in which it takes place. In the past, armed groups have been seen as a springboard for their leaders to high-level positions in the military, government or national politics. These setups generally benefited high-ranking individuals, turning ordinary soldiers into tools for their own professional gain.

Challenge 3: The fundamental lack of trust between the government, armed groups and communities. The government and army have reneged on promises to armed groups in the past, particularly regarding demobilization and community reintegration.

Challenge 4: The overall reintegration delays for ex-combatants. The willingness of ex-combatants to demobilize and reintegrate is naturally greatly influenced by the availability of alternative livelihoods and employment. In the Gao region the reality faced was that ex-combatants became a threat to the continuation of the DDR process.

Challenges 5: Poverty and community violence.

In a situation of extreme socio-economic difficulties, the financial flows to which demobilization and reintegration programs are attached have produced benefits for the leaders of armed groups, combatants and political elites.

It is therefore not surprising that many communities perceive reinsertion/ reintegration programs as a reward for those who engage in armed conflict, thus oftentimes resulting in one of the reasons for the rejection of ex-combatants by the host communities.

In conversation with Ndiaga Diagne

Ndiaga Diagne

DDR Chief with the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA).

Mr. Diagne has in the last 20 years gained extensive experience in the field of DDR, and is adept in political and military dynamics of conflict given his background and work in MINUSMA combined with the expertise gained in ONUCI, MONUC and MONUSCO.

ON THE FIELD: SUDAN

With the ongoing conflict in Sudan and a request by the authorities that the UN Integrated Transition Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS) depart, the Council terminated the mission’s mandate on 1 December 2023. Sudan’s transition has witnessed significant political shifts, with the ousting of long-standing leadership and aspirations for democratic governance. The UN’s involvement in Sudan highlights the necessity of adapting strategies to unique political contexts. Lessons learned underscore the importance of supporting institutions that promote inclusive governance and addressing historical grievances. The transition in Sudan reinforces the idea that sustainable peace requires a delicate balance between justice, reconciliation, and institutional capacity-building.

Zurab Elzarov

Chief of Learning, Leadership and Management Development and the Head of Mobility Implementation Team in the Office of Human Resources, DMSPC

Zurab leads the planning and implementation of learning and skills development initiatives and supports the execution of the new approach to staff mobility. Prior to his appointment with DMSPC, Zurab Elzarov held managerial positions with peacekeeping missions in Africa. He also served with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Eastern Europe.

Islika Borbor Sisay

Presently the DDR Advisor with UNITAMS (Sudan).

Islika has worked in Sudan, Afghanistan, and Sierra Leone as a DDR practitioner for more than 15 years. Islika was a co-recipient of the 2014 UN 21 Award in October 2014 with UNAMID. Islika has published two policy practice briefs (PPB) on Community Stabilization and SALW control in Darfur in the academic journal “Academia Letters” (2022) and the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), in September 2022.

In conversation with Zurab and Islika

Drawing from your personal experience in Sudan, what are the main challenges that come to mind when reflecting on key transition moments?

Zurab: Firstly, it is important to establish partnerships and work closely with relevant UN agencies from the onset of DDR activities. In Darfur, the Mission enjoyed strong cooperation with UNDP from the very beginning and worked closely together in planning the DDR activities. World Food Program (WFP) and International Organization for Migration (IOM) were also reliable partners in implementing reinsertion activities for ex-combatants. Therefore, the transition of traditional and second-generation DDR activities in Darfur went well to a great extent.

Nevertheless, we should always remind ourselves that any successful DDR programme must be led by the host government. The government counterparts should see themselves as the owners of the DDR processes and provide leadership and vision in planning the DDR activities. In different contexts this may require different action, ranging from capacity building of relevant government representatives to co-funding of DDR activities with the government, and supporting the government counterparts with the development of DDR strategies. Without the government’s ownership of these processes the impact of our DDR activities might be limited and less sustainable.

It is also essential that various actors and counterparts manage the expectations of post-transition support they would receive from a follow-up mission or UN agencies. The future DDR activities should be carefully crafted based on the available resources and the specific mandates of all actors involved.

Islika: Transitioning UN mission tasks to the UNCT presents challenges related to capacity, resources, interests, and mandates, notably DDR within the broader political process. Addressing these concerns assertively and strategically is imperative for seamless transitions. The discontinuation of the State Liaison Functions (SLF) transition mechanism for UNAMID post-closure highlights the challenges a post-audit evaluation exposed, emphasizing the imperative for proactive measures and comprehensive solutions. Additionally, transferring mission activities to post-conflict governments poses challenges requiring increased resources, capacity, and political will. The uncoordinated and independent execution of UN mission substantive mandates also complicates the transition to the UNCT or government.

Based on past experiences, what insights can you share for colleagues and senior management working on DDR/CVR processes supporting transitions?

Islika: Exploring how DDR/CVR can effectively support transitions and prevent conflict recurrence is crucial. Identifying alternatives for managing weapons and combatants, post-conflict and identifying and evaluating potential DDR partners and capacities is pivotal for a smooth transition. This proactive approach ensures the identification of capable partners beyond conventional choices like the UNCT, such as relevant ministries and institutions and integrating planned and ongoing DDR/CVR programs. Capacity-building and knowledge transfer to the selected partners is critical for ensuring a seamless transition and sustained post-conflict peacebuilding.

Zurab: In Sudan, for example, the Joint Transition Action Plan (JTAP) developed by UNAMID jointly with the UN country team based on the situational analysis, identified three main causes of the conflict in Darfur for which it made sense for the UN to work jointly – land dispute resolution and rights, Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) and refugee returns, and scarcity of resources.

Another important aspect is the establishment of effective coordination structures to support the transition process. A Joint Transition Cell (JTC) was established in Darfur which supported UNAMID and the UNCT to spearhead and provide oversight on broad transition guided by JTAP. The JTC brought together UNAMID and UNCT to ensure implementation of planned interventions under each workstream, including reporting on progress.

What is also important is to be forward-looking, innovative and willing to experiment when planning and implementing the transition process. During its transition, UNAMID and the UN country team in Sudan established State Liaison Functions (SLFs), seconding UNAMID staff and using the assessed peacekeeping budget for programmatic activities implemented by UN agencies.

In terms of knowledge management, a system was timely established to manage the data and knowledge transfer from UNAMID to UNCT, including datasets related to PoC, DDR, rule of law and mediation of inter-communal conflicts.

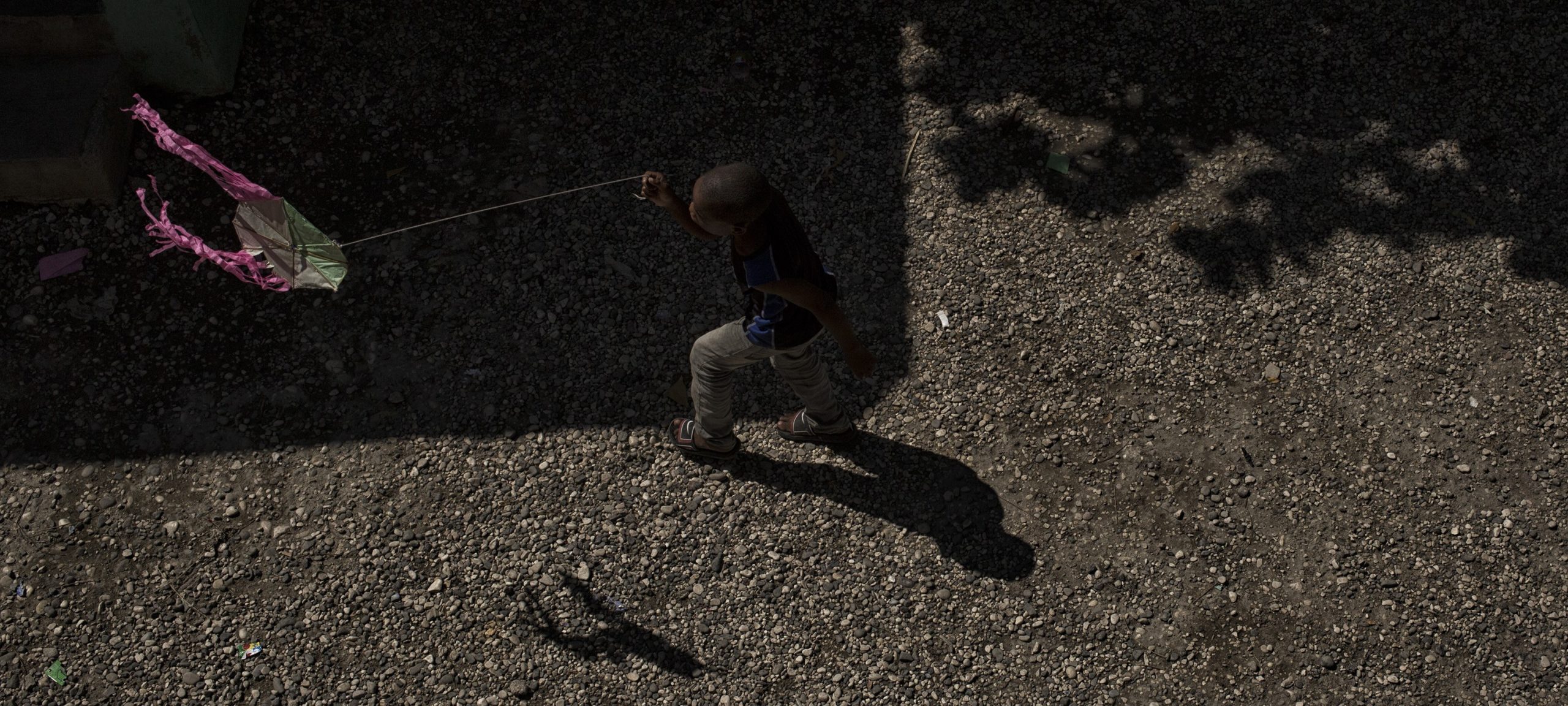

6. MUNIGI CAMP

In order to understand how DDR projects work in practice, let us zoom into the Munigi camp, a short distance away from northern Goma, North Kivu in DRC. The Munigi camp served as one of the main transit camps since the establishment of the DDR / RR-CVR section in 2010, more than 10,000 foreign and congolese ex combatants have been registered, repatriated and have received reintegration support.

Ndiaga Diagne

DDR Chief with the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA)

“From my point of view, since we’re moving towards a transitions phase, it is important to consider transferring camp management to national actors”

5.KEY LESSONS

Whilst there may not be a one-size-fits all approach to transitions, as the examples of DRC, Haiti, Mali, and Sudan, , have demonstrated, the insights provided in this Bulletin have highlighted the existence of several strategies and practices which have proved beneficial in past transition processes. DDR/CVR/Weapons and Ammunition Management (WAM) practitioners must recognize that transitions provide an opportunity to establish meaningful partnerships and to ensure full implementation of national ownership. Transitions allow DDR/CVR/WAM practitioners to collaboratively redefine priorities, roles, and responsibilities with national institutions, consolidating gains through new cooperation modalities.

Sustainable Peacebuilding

Ensuring that the transition process contributes to sustainable peacebuilding is crucial. This involves addressing the root causes of conflicts and building institutions that can maintain stability, specifically in WAM and CVR in the context of DDR.

Inclusive Processes

Inclusive and participatory processes are essential for successful transitions. Building strong partnerships requires effective communication and coordination with local partners, including community-based organizations early in the process. Establishing a solid understanding of challenges and achievements with national entities, UN Agencies Funds and Programs (AFPs), regional organizations, and institutions is vital and sustained support aligned with government objectives a priority.

Coordination and Communication

Close coordination and communication between DDR practitioners, UNCT, and Resident Coordinators contribute to a positive transition momentum. Systematic inclusion of DDR/CVR/WAM in Common Country Analyses, UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Frameworks, and Peacebuilding Funding eligibility processes is essential. This coordination facilitates joint planning, identifies capacity gaps, and explores options to address them, including funding shortfalls, in line with the humanitarian-development-peacebuilding nexus approach. Early engagement with key actors, including UN Security Council resolution penholders, the DCO, relevant development actors, and IFIs like the World Bank, is critical to ensuring a shared understanding of challenges and securing financial support for strategies aligned with government priorities.

first mentioned earlier on in the doc [EM1]

Adaptability and Flexibility

Recognizing that each transition is unique and requires tailored approaches is essential. Flexibility in strategies allows for adapting to changing circumstances.

Rule of Law and Governance

Strengthening the rule of law and governance structures is often a key aspect of transitions. This includes building effective and accountable institutions to ensure stability.

Security Sector Reform

Managing the transition of security forces is critical. Reforming and professionalizing security sectors helps prevent a security vacuum and promotes stability.

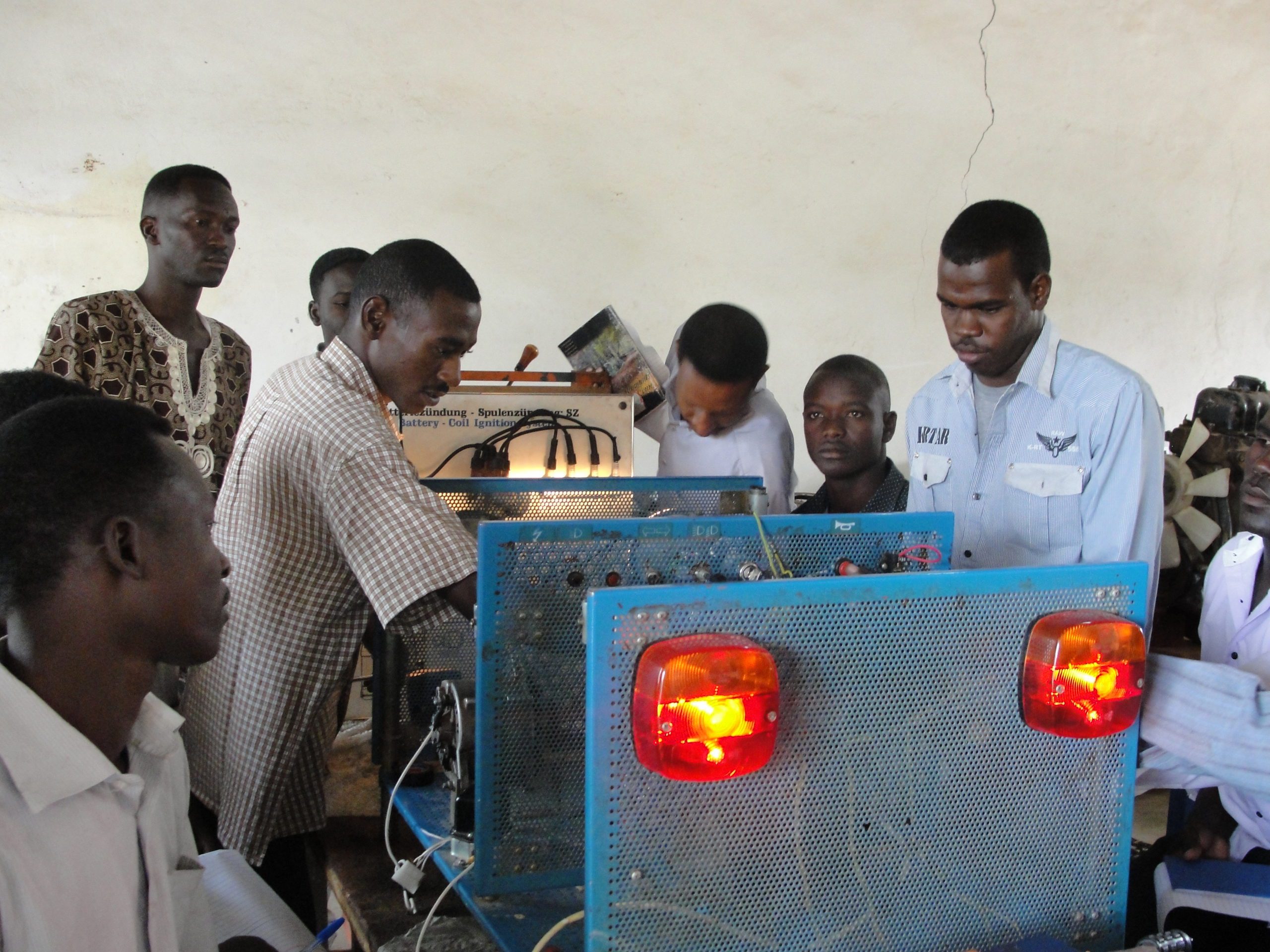

Capacity Building

Building local capacity is an ongoing process. Providing training and support to local institutions and communities enhances their ability to manage their own affairs post-transition.

Resource Mobilization

Adequate and sustained financial and logistical support is necessary for successful transitions. Securing commitments for long-term assistance is important for post-transition stability.

Monitoring and Evaluation

Establishing robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms helps assess the impact of the transition process and make necessary adjustments.

Bujar Alickaj

“In my opinion, clear and consistent communication is absolutely key in transition processes”

IDDRS UPDATES

All modules of the IDDRS have now been finalized and validated by the IAWG-DDR since the publication of the last DDR Bulletin. including module 5.10 regarding Women, Gender and DDR and module 6.20 addressing Transitional Justice an DDR. The operationalization includes disseminating the updated standards with practitioners in the field to support work on the ground.

Two modules have been validated by the IAWG-DDR since the publication of the last DDR Bulletin, namely 5.10 Women, Gender and DDR as well as 6.20 Transitional Justice and DDR.

Recent publications

Climate Change and DDR Fact Sheet, which provides a snapshot of the Climate Change and DDR Project.

Upcoming events and trainings

Training Opportunities

Upcoming opportunities include:

Integrated DDR Training Group

The Integrated Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration Training Group (IDDRTG) is a community of a total of 20 international organizations and training institutes with a common goal of developing and sharing training materials relating to the DDR-field.

The website is regularly updated with upcoming training events: https://iddrtg.org

Laying the ground for Peace: A Holistic Approach to Community Violence Reduction

27 May – 31st May 2024

Stans

-

DDR Planning course

31 May – 7 June 2024

Stockholm, Sweden

TOOLS & RESOURCES

With thanks to Thomas Kontogeorgos, Kwame Poku, Markella-Eleonora Mantika, Beatrice Hagan, Cheriff Musombo, Osama Abdelaziz Mahmoud Abbas, Aimee Therese Faye Diop, Louise Bosetti, Jeanne Ni Bhriain, Janvier Mushengezi and the DDRS team. Special thanks to all those who have worked and/or are currently working on UN DDR/CVR transitions.