HIGHLIGHTS FROM THIS NEWSLETTER ISSUE

BY DPO-DDR SECTION

READ THIS

B DDR in UNAMID – A Retrospective

“I had no tailoring skills before,

but now I run my own tailoring

workshop. My daily income is

sufficient enough to live a good life.

CLIPs have significantly changed

my life.” Rawda Mohamed

(UNAMID CLIPs Beneficiary)

LISTEN TO THIS

Career advice from Manjula Wijedana, a DDR Field Officer

WATCH THIS

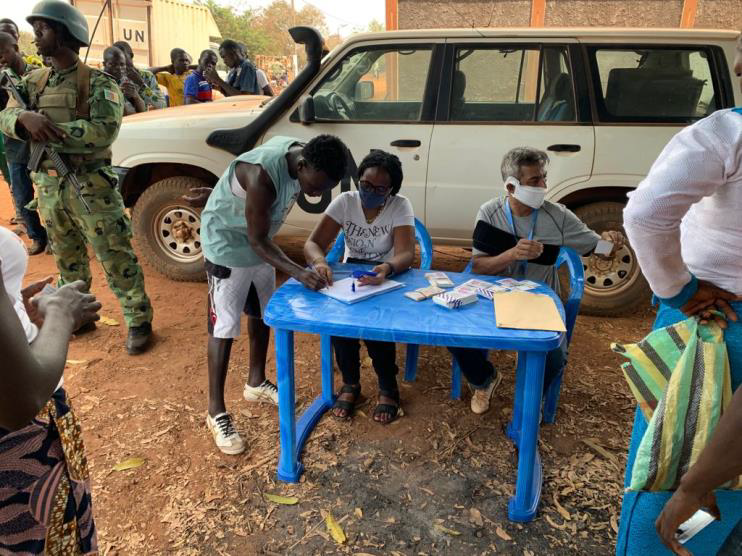

CVR projects in Central African Republic: insights from beneficiaries

CONTENTS

In Focus:

a4p third anniversary

1.

DDR in UNAMID – A Retrospective

2.

field updates

3.

policy and partnership updates

4.

operational funding overview

5.

Testimonials From the Field

6.

IDDRS Updates

7.

Upcoming

a4p third anniversary

Action for peacekeeping (a4p)

As part of the UN’s multifaceted approach to peace, UN peacekeeping is a critical contributor to lasting peace and a powerful demonstration of multilateral cooperation. UN peacekeepers face many challenges, including protracted conflict, elusive political solutions, increasingly dangerous environments, rising peacekeeping fatalities, and broad and complex mandates.

In response to these challenges, the Secretary-General launched the Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) initiative and the Declaration of Shared Commitments in September 2018 in order to refocus peacekeeping efforts and reaffirm political commitments to peacekeeping operations.

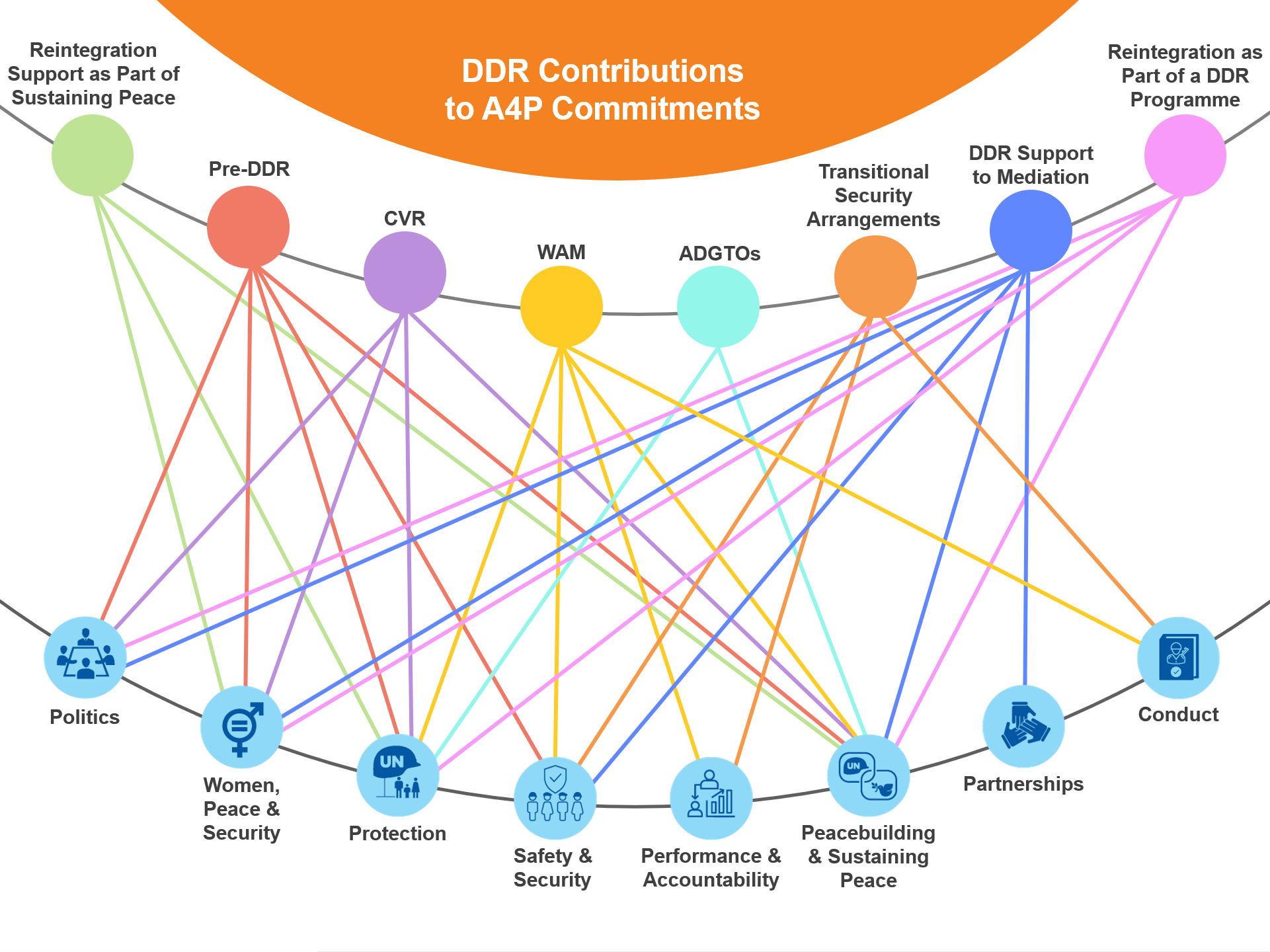

Three years in, the Declaration of Shared Commitments remains the roadmap and reference for our collective efforts to strengthen peacekeeping. It has benefited from broad political support and proved immensely valuable in providing common purpose and focus between all peacekeeping actors. In support of the A4P initiative, all facets of the new UN approach to DDR continue to substantially contribute to the commitments of the A4P agenda, especially the commitments for sustaining peace and women, peace, and security.

The new UN approach to DDR has evolved due to similar challenges in the changing contexts of conflict. These challenges include the absence of comprehensive peace agreements, fragility of existing peace agreements, increase in non-state violence and the prevalence of localized conflict, the designation of armed groups as terrorist organizations (AGDTO), continuing fragmentation and multiplication of armed groups, the rise of transnational armed violence and criminal networks, and the impact of epidemics and pandemics in conflict settings.

In response to these challenges, DDR has expanded to include DDR-related tools, including DDR support to medication, transitional weapons and ammunitions management (TWAM), community violence reduction (CVR), and pre-DDR. The flexible tools allow for further options in contexts where the preconditions for a traditional DDR programme are not present. In this way, these tools can be used ad hoc, to supplement or complement DDR programming.

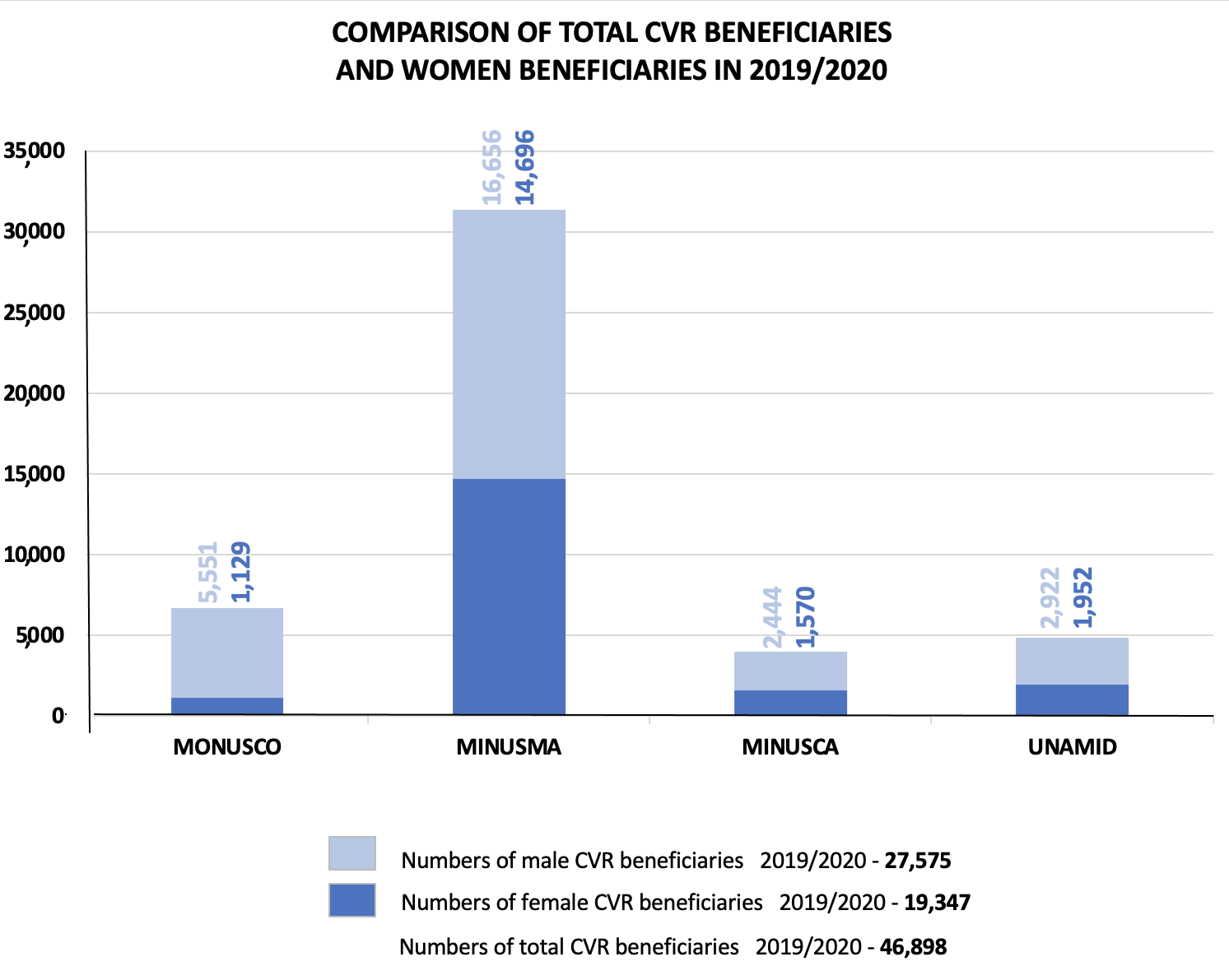

These DDR-related tools provide the DDR practitioners new opportunities to contribute to the A4P agenda. For example, tools like CVR have proven to be central in allowing practitioners to adapt DDR to many different and evolving operational contexts. CVR supports communities by strengthening capacities for the prevention and mitigation of violence and the reintegration of ex-combatants. Through these DDR related tools, in complement to humanitarian and development efforts, DDR contributes to multiple A4P commitments including, support to political solutions, women, peace and security, the protection of civilians, and sustaining peace.

In short, the expansion of DDR and the flexibility of DDR-related tools in the new UN approach now allows for stronger linkages to the goals and commitments of the A4P agenda. At the same time, the A4P commitments and A4P+ priorities themselves ensure that DDR remains effective and efficient in the challenging operating environments DDR practitioners now find themselves.

COUNTRY EXAMPLES OF DDR CONTRIBUTIONS

Click through the slides to learn more about

DDR Contributions to A4P Commitments

CVR PROJECTS IN MALI AND CAR: INSIGHTS FROM BENEFICIARIES

DDR in UNAMID – a Retrospective

No programme is a failure. The only time you can call a programme a failure is when there is a relapse of conflict in that country. This hasn’t occurred in Darfur.

The United Nations- African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) has come to an end. Yet, as Sudan welcomes a newly-established Special Political Mission (United Nations Integrated Transitional Mission in Sudan – UNITAMS), it is crucial to reflect on the mission and the role DDR played during its time under UNAMID.

This article provides a comprehensive retrospective of DDR in Darfur. It touches upon DDR decisive presence when signing the Peace Agreements, the limitations of launching DDR programs in non-inclusive treaties and the impact of cross-fertilization among missions. Darfur is in fact a story of how DDR had to adapt to the context and shape itself to the country dynamics to endure.

FIRST STEPS TOWARDS PEACE

The Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) was the first major milestone in the long peace process. The Government of Sudan together with a major rebel faction, the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A), signed this agreement under the support of the African Union (AU), the UN and other partners in 2006. DDR was central to the DPA final security arrangements. UN DDR advisors were specifically involved in the Darfur peace talks, they provided technical assistance to the parties and supported the drafting of the agreement. Their presence ensured that several DDR related tasks were included in the DPA. At the time, it was the AU Mission in Sudan (AMIS) that undertook such tasks which were subsequently inherited by the joint UN/AU mission in Darfur (UNAMID).

Nevertheless, several areas in the DPA required clarification and further negotiations on the ground. For instance, the establishment of a clear institutional framework to plan and manage the DDR process, including representation of the UN in these institutions at the highest level; links with the other Sudanese DDR programmes; the role of the National DDR Commission in Darfur and more. In hindsight, it is now evident that less ambiguity in the DPA would have allowed the implementation of a more transparent programme and assisted in better defining the Mission’s mandate and resource requirements for DDR.

CREATION OF UNAMID

As anticipated, in 2008 the AU together with the UN deployed an unprecedented hybrid operation named UNAMID under the Security Council Resolution 1769 (2007). The resolution comprised a mandate which included the “establishment of the DDR programme called for in the DPA” (S/2007/307/Rev.1). CVR, then in its early stages in Haiti, was not mentioned in the mandate. Interestingly, while CVR was never explicitly included in the UNAIMD mandate, CLIPs and subsequent stabilization activities were implemented under the DDR mandate, as both the interventions served the same strategic objective.

NEW AGREEMENT, old challenges

A subsequent round of negotiations, which lasted two and half years in Doha, Qatar, led to the signing of the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (DDPD) on 14 July 2011 by the Government of Sudan and the Liberation and Justice Movement (LJM). During the negotiations, UNAMID provided technical expertise, including DDR experts, who played a significant role in assisting the creation of the final security arrangements provisions of the DDPD agreement. DDR tasks were mentioned multiple times in the DDPD.

However, the DDPD, similarly to the DPA, was non-inclusive, given that the two main armed movements i.e., Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and the Sudan Liberation Army/Abdul Wahid (SLA/AW) along with other non-signatory movements did not take part in the discussions or signing and refused to commit to the resumption of talks. Aderemi Adekoya, UNAMID Chief of Service – DDR/Deputy Chief of Staff, and Isa Macedoine, UNAMID DDR field officer, both confirmed in separate interviews that this is what prevented the implementation of many elements in the agreement, posing a serious challenge for a viable DDR programme in Darfur to take off. Nevertheless, Mr. Adekoya also mentioned that a DDR programme for the LJM combatants was supported by UNAMID, however, on a limited scale. Overall, 11,000 combatants (signatory armed groups) were demobilized in Darfur, despite challenges.

Moreover, efforts were made through the DPA and DDPD to achieve peace in Darfur. Both documents made provisions for the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of ex-combatants and addressed the issue of civilian small arms proliferation. Yet, implementation, due to the non-inclusive nature of the peace agreements, was the challenge.

LEARNING FROM HAITI

Given that DDR activities mentioned in the peace agreements did not take off fully, an alternative path had to be designed. In January 2012, the UNAMID DDR Section and UNHQ DDR colleagues visited the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), where the first Community Violence Reduction (CVR) programme – one of DDR measures – had been established in 2006. This visit was a decisive moment for the reshaping of the DDR process in UNAMID according to Mr. Adekoya. There, the UNAMID DDR team familiarized itself with the CVR methodology and brainstormed with MINUSTAH CVR colleagues about the kind of projects that could be established in an environment where no real economy exists. Following the visit, UNAMID DDR Section components adapted the CVR approach to Darfur’s context and developed distinctive CVR measures under the moniker CLIPs (Community-based Labor-Intensive Projects). Cross-fertilization would soon lead to a DDR success in UNAMID (see Voices of Darfur).

DDR METAMORPHOSIS

By mid-2012, UNAMID had operationalized CLIPs, a community stabilization and violence reduction programme that bridged the gap between jobless youth and lack of training and employment opportunities in the country. Mr. Adekoya remarked that “through CLIPs, we provided youth with skills so when an opportunity for a job is created by the government they can be absorbed as they possess the capacities needed.” Moreover, the projects implemented were twofold. The provision of vocational skills training on specializations that are high on demand on the local market (e.g., welding, metal works, computer training, carpentry) so youth participants could later open their own business. Alternatively, the engagement of at-risk youth in temporary employment opportunities, specifically, construction activities where learning was provided on the job while building schools, hospitals.

As it occurred in Haiti, CVR was a success in Darfur. As a recognition of its contribution to peace and stabilization in Darfur, in October 2014, UNAMID’s CLIPs programme received the UN 21 Award, for Outstanding Vision. The UN 21 Awards provide “recognition to staff members for innovation, efficiency and excellence in the delivery of the Organization’s programmes and services” (UN21, 2015). Also, in 2015, the section was declared the Country Winner for Sudan of the 2014 Saville Foundation Pan-African Awards for Entrepreneurship in Education.

One of many successful stories is of Rawda Mohamed who received training in tailoring and sewing. She said, “I had no tailoring skills before, but now I run my own tailoring workshop. My daily income is sufficient enough to live a good life. CLIPs have significantly changed my life. I consider myself socially and economically empowered” (see the source article by Elzarov Z.).

In the beginning of 2015, the programme evolved from the initial concept of CLIPs into Community Stabilization Projects (CSP). Until 2019 the CSPs focused on promoting community security, strengthening governance, institution development and community empowerment, amplifying access to basic social and economic services and creating durable solutions for conflict-affected communities. Isa Macedoine reminisced that “by reorienting the DDR program into CLIPs and later into CSP we gained the flexibility needed to help stabilize fragile communities and reach out to vulnerable groups, including women, instilling hope of life outside of conflict.”

CLIPs and subsequently CSP contributed to building confidence and changing perception about UNAMID. From 2012 to 2019 they supported over 10,000 youth and vulnerable community members, becoming one of the most important and widely implemented UNAMID programmes in Darfur to assist the Government of Sudan to address the socio-economic exclusion of youth-at-risk. By promoting alternative livelihood and capacity building opportunities, strengthening the resilience of local communities and bolstering peacebuilding, these projects reduced community violence, prevented the recruitment of youth in armed movements and combated unemployment, so to build the foundation for long-term development and stability.

When starting the DDR programme the Sudanese government thought that DDR only meant providing money to ex-combatants or collecting their weapons. Later the government realized that DDR programs are much more and thanked us – the DDR Team – for providing youth and ex-combatants with skills they can make use of in future jobs, running medical screenings, supporting food assistance and much more.

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED?

In May 2019 the DDR programme implemented in Darfur was concluded and, on 31 December 2020, UNAMID terminated its mandate. While not officially referenced, CVR-type activities directly contributed to the implementation of UNAMID’s mandate related to DDR. In the view of Zurab Elzarov, UNAMID senior DDR officer, “we – the DDR team – tried to explain to the general public and the government the link between CVR and DDR but clarity of how CLIPs projects are part of a CVR programme and CVR is a part of the greater DDR programme was not achieved. A lesson learnt is to better familiarize everyone – from the very beginning – on CVR and how it links to DDR.” This will avoid controversies on what to account as a DDR success as it occurred in UNAMID.

Nevertheless, evidence highlights that the projects contributed to the social and economic development of Darfur, which helped reduce violence and promote peace. Hence, through education and employment opportunities, communities became more secure and CVR beneficiaries chose not to use weapons, focusing on rebuilding their communities.

For instance, in Nyala, South Darfur State, every year over 100 young women and men have benefitted from CLIPs vocational skills training. Zakaria Idris, is one of these and expressed how: “It was a dream. Now, it is a reality. I work as a car mechanic. My work is profitable and enjoyable. I have many customers from different communities of South Darfur. I see myself being a useful citizen and adding my input into stabilization of my country.” Yet most interestingly he added that “I thank UNAMID for not just helping me become a car mechanic, but for that I also changed and better understand that weapons are most likely to harm us than bring us any good.” Thus, emphasizing how CLIPs projects also raised awareness about disarmament within communities.

DDR in Sudan is a tale that carries on beyond UNAMID. Following the Juba Peace Agreement in October 2020, the new and significantly smaller Special Political Mission – UNITAMS – has a steep mountain to climb to deliver on its broad mandate which includes DDR. But the recent political developments in Sudan have gained further momentum and many see it as an historic opportunity to finally curb the violence that affected the country for decades. Learning from past mistakes needs to be matched with both innovative and durable solutions. With both CVR as well as weapons and ammunition management at the core of such a new approach, there is reason for a newfound optimism about the future of DDR in Sudan. The story continues.

You don’t need to have weapons to still have life, people use weapons to protect their families, villages, their life circle, but if you have an appropriate Rule Of Law many people will not remember to take their arms. If we are able to put in place infrastructures that will support the growth of the country coming out of war, then we will see significant changes.

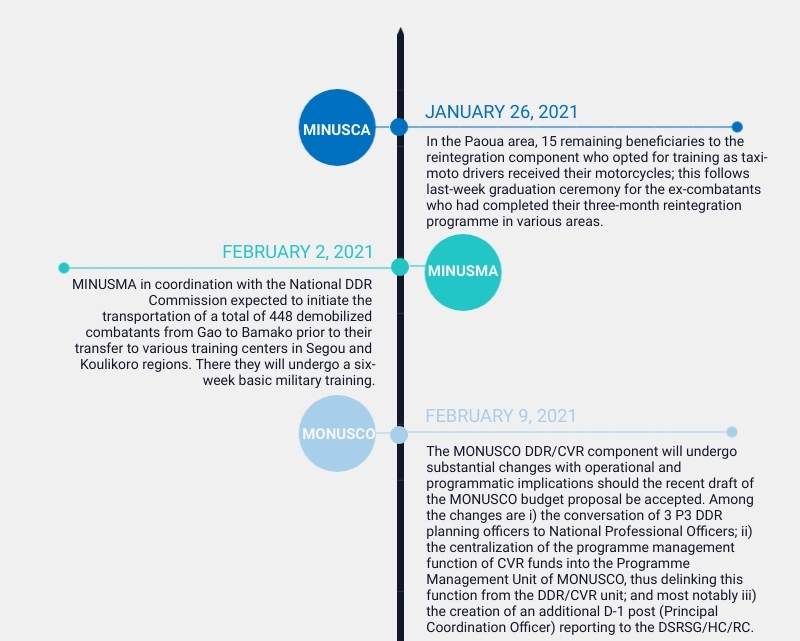

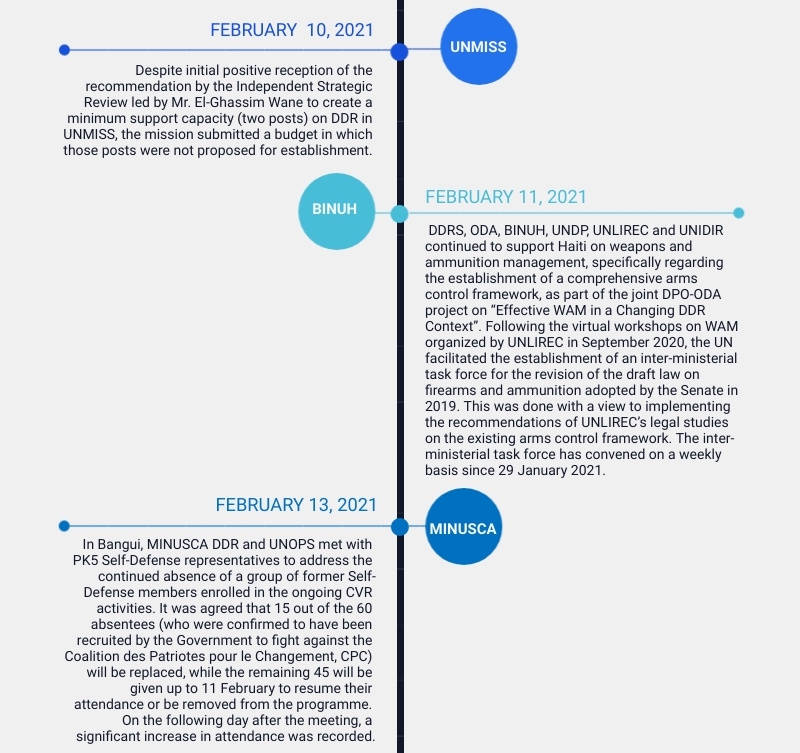

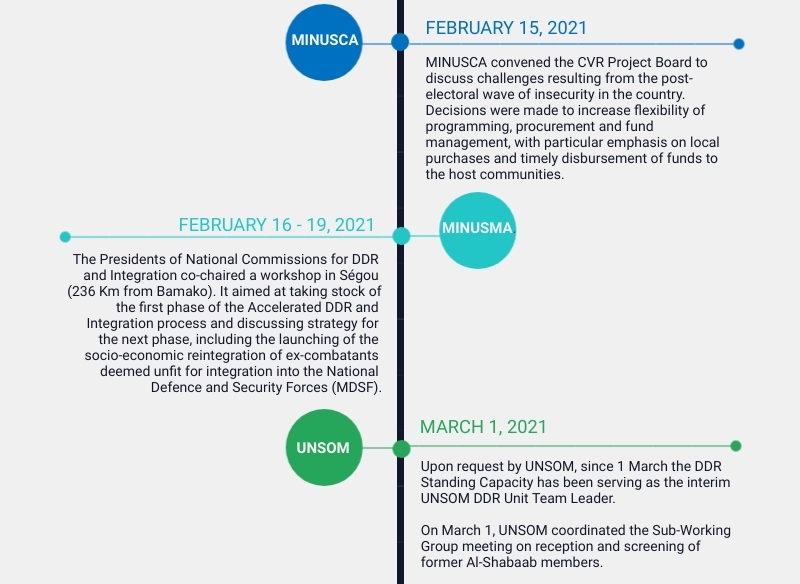

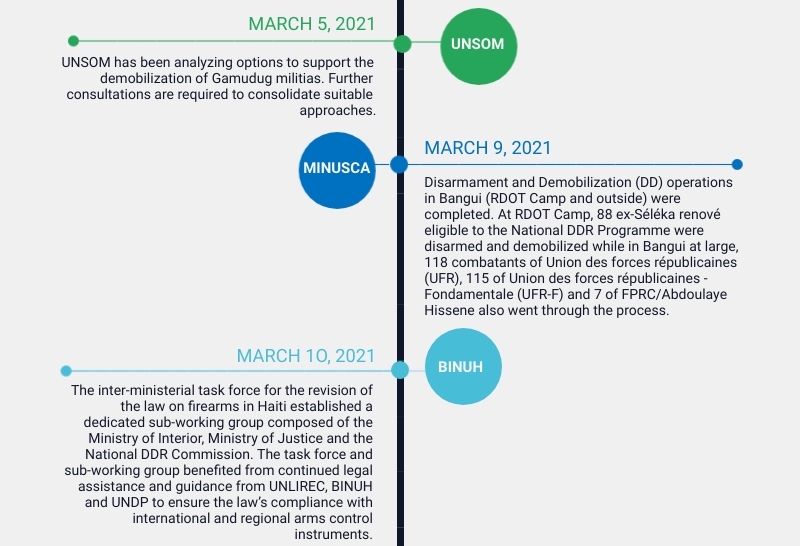

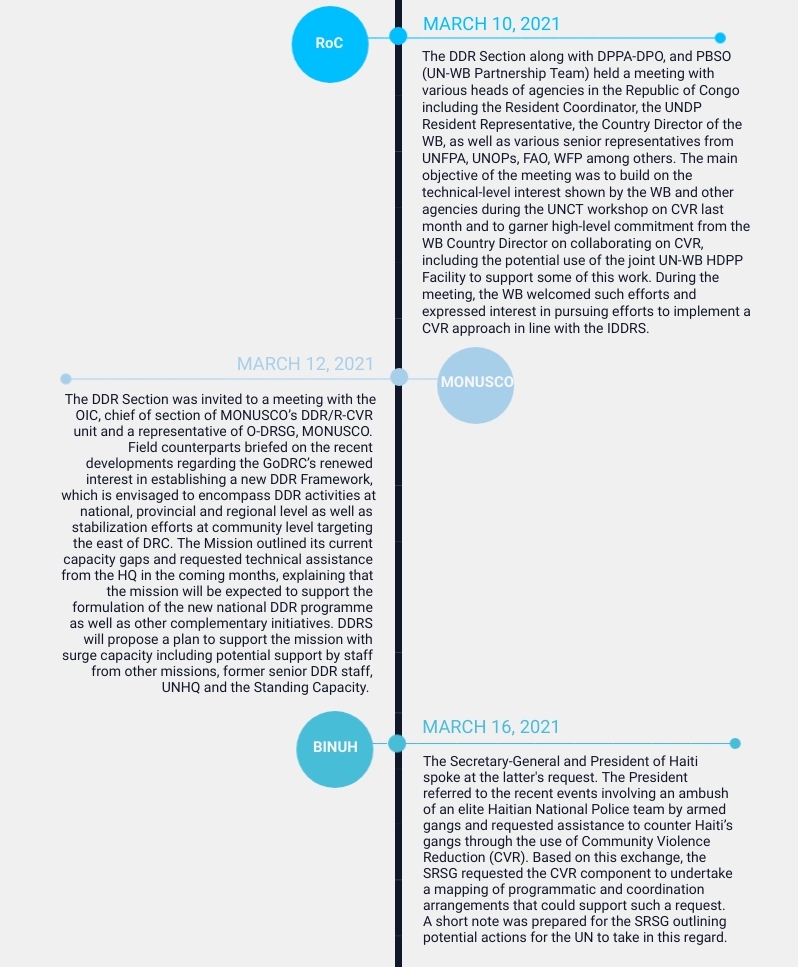

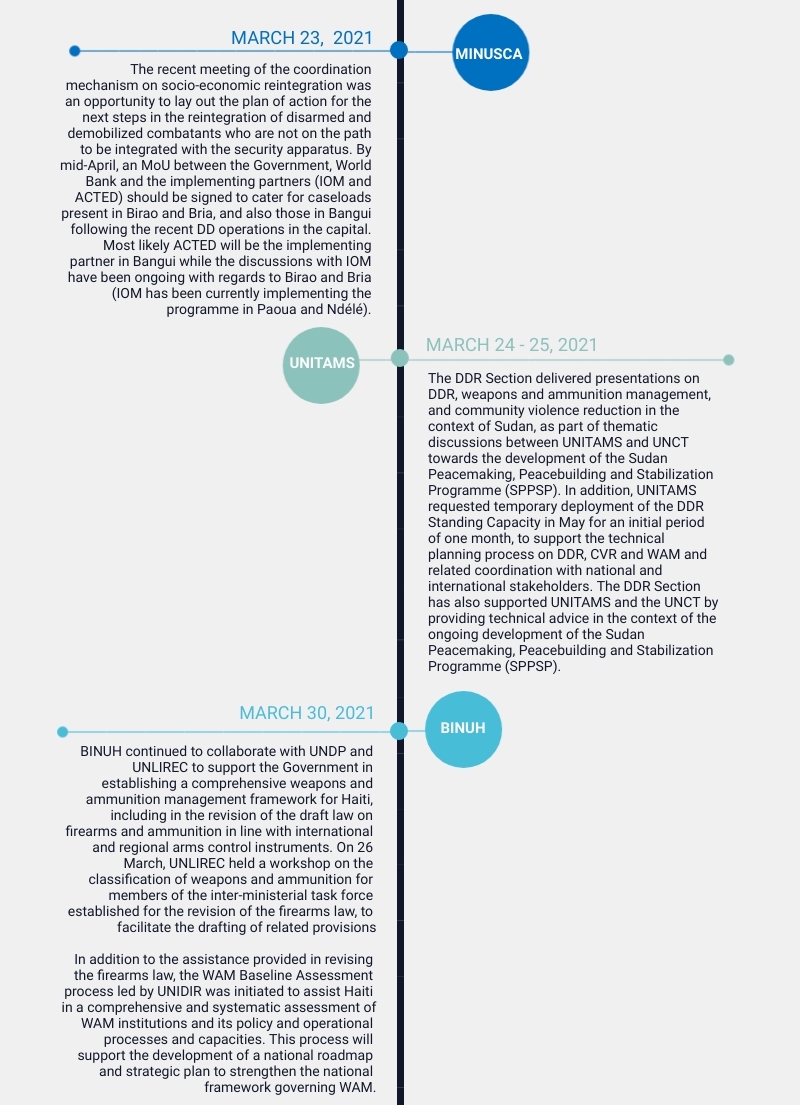

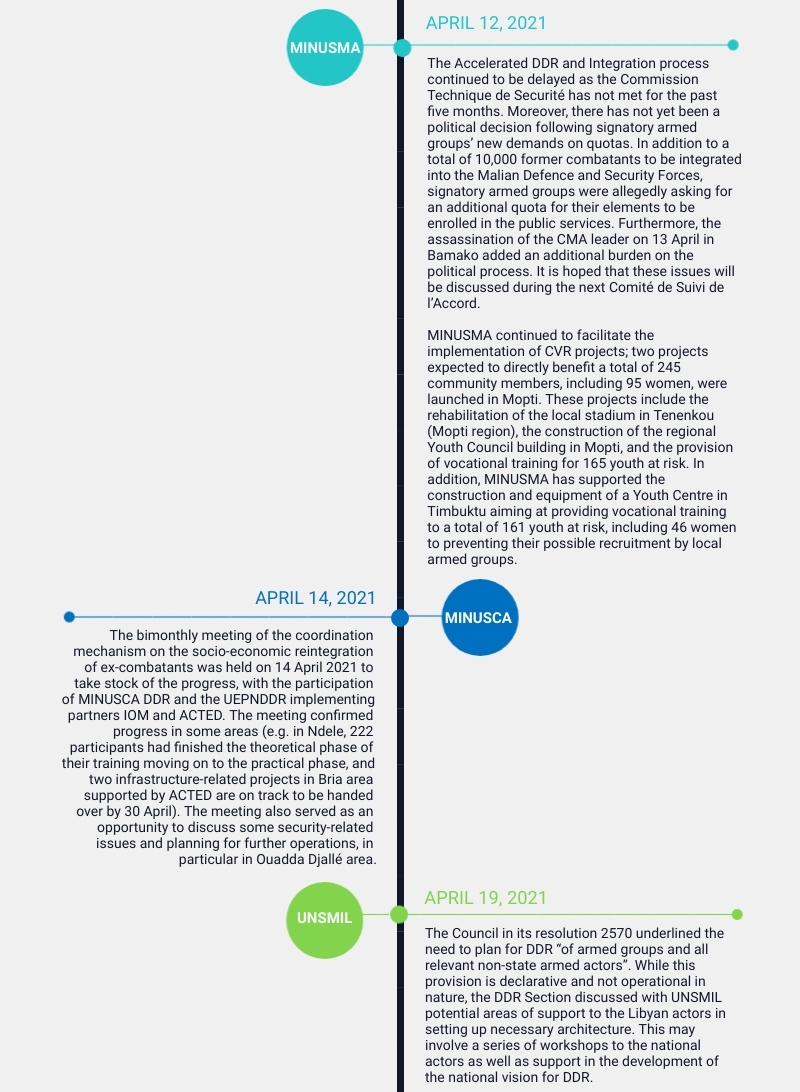

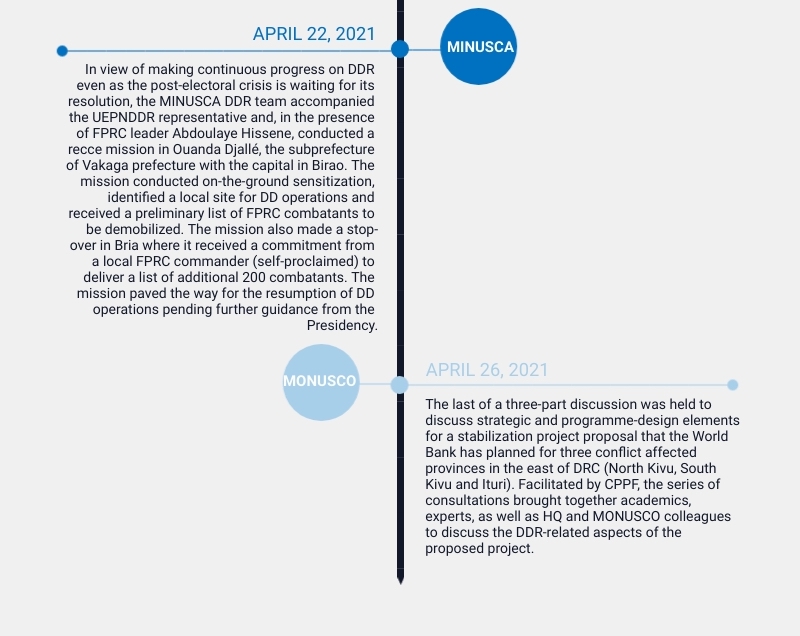

FIELD Updates

MONUSCO peacekeepers are distributing pamphlets while patrolling in Jiba, Ituri to encourage combatants to join the DDR process.

policy and partnership Updates

CVR – SOP

The joint DPO-DPPA-DOS Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) on Community Violence Reduction (CVR) in DDR Processes, developed by the DDR Section (DDRS), has now been signed by the USGs of DPO (Jean-Pierre Lacroix), DPPA (Rosemary DiCarlo) and DOS (Atul Khare).

The new SOP aims to provide procedural guidance and a harmonized approach to the management and implementation of CVR programmes funded, wholly or partially, by the assessed budgets of field missions. The SOP reflects good practices from programmatic activities implemented by field missions and it specifically builds on the revised Integrated DDR Standards which set out guiding principles for CVR programmes.

CVR is a flexible approach to preventing and reducing community violence. CVR programmes can be implemented before, during and/or after a DDR programme as they are designed to contribute, by way of complementarity, to the strategic objectives of the DDR programme. CVR is distinctively bottom-up in orientation and serves as a short-term security and stability measure helping facilitate a better relationship between target communities, the local and national governments and the mission, which may improve the implementation of the broader DDR process. Given the added value of CVR to DDR processes has already for some time been broadly acknowledged, the SOP fills the long-standing guidance gap on CVR.

The SOP is binding for all DDR/CVR staff in peacekeeping operations who are involved in the initiation, planning, execution, and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of CVR programmes. Other partners and contexts are also recommended to adhere to the SOP, which would serve to ensure effective coordination within the United Nations country team and to avoid duplication of projects in the same intervention area.

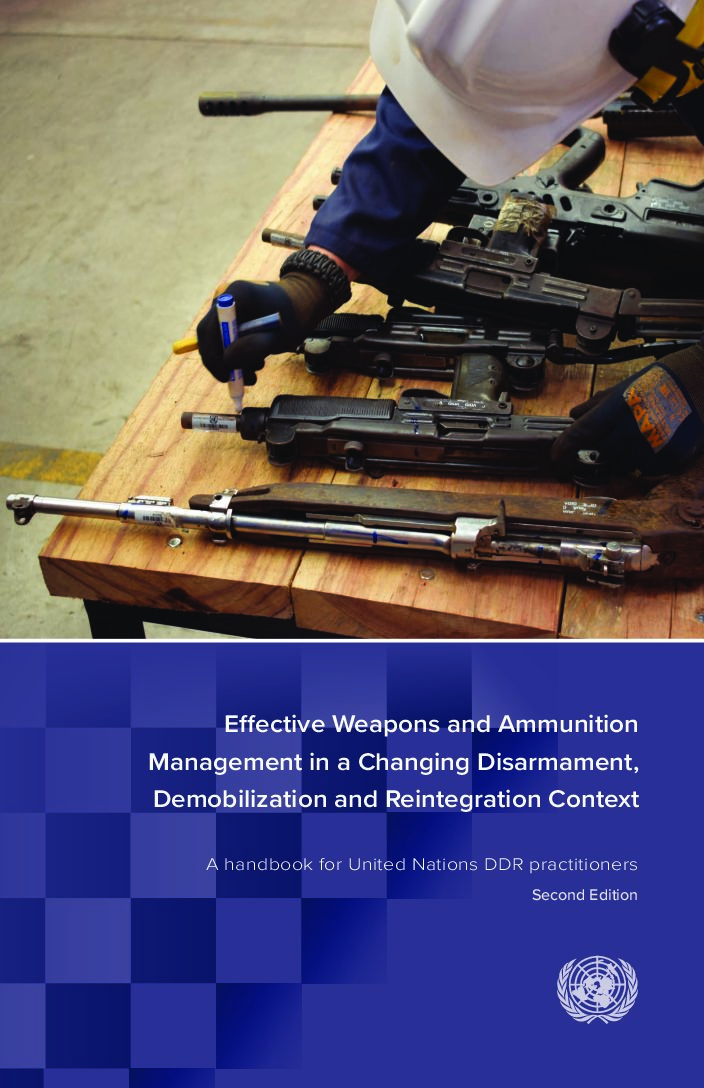

Weapons and Ammunition Management (WAM)

DDRS and the Office of Disarmament Affairs (ODA) released the 2nd edition of the UN Handbook for DDR practitioners on “Effective WAM in a Changing DDR Context”. First published in 2018 and developed as part of a joint initiative between Department of Peace Operations (DPO) and ODA, the Handbook provides DDR practitioners with practical guidance to design and implement state-of-the-art disarmament and WAM initiatives as part of integrated DDR processes, including through the use of DDR-related tools such as CVR. The Handbook draws upon good practices and innovative approaches developed in the field, as well as relevant international standards and guidelines.

To mark the launch of the publication, a virtual event was held on 14 April, bringing together Member States, UN entities, regional organizations and non-governmental organizations.

The event was opened by Ambassador Rüdiger Bohn, Federal Government Commissioner for Disarmament and Arms Control of the German Federal Foreign Office. Under-Secretary-General for Peace Operations Jean-Pierre Lacroix and Under-Secretary-General and High Representative for Disarmament Affairs Izumi Nakamitsu offered welcoming remarks via video messages.

Savannah de Tessières, author of the Handbook, introduced the 2nd edition that reflects relevant developments at the policy level, including the revised Integrated DDR Standards and the MOSAIC module on SALW control in the context of DDR, and ensures consistent gender mainstreaming as well as systematic integration of youth considerations.

The virtual event also showcased concrete support currently provided to national authorities in Haiti in the framework of the joint DPO-ODA technical assistance mechanism. The United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Regional Centre for Peace, Disarmament and Development in Latin America and the Caribbean (UNLIREC) and United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) demonstrated strong multi-partner collaboration in assisting the Haitian authorities in the establishment of a comprehensive WAM regulatory framework, in line with international and regional arms control instruments.

DDR Revision of its SOP on M&E

On 25 February, the DDRS conducted a preliminary presentation to the Guidance Focal Point Group (GFPG) on the revision of its Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) on Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) for DDR.

In responding to the Member States’ call for increased transparency and accountability, the DDR Section was in 2010 among the first entities in the UN Secretariat to develop its own guidance on M&E. In line with the Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) Initiative, the revision aims at further promoting a culture of performance and accountability. The revision builds on an in-depth evaluation conducted by DPET on M&E practices in DDR programmes in 2017-18 and subsequent consultations. The DDRS is also working with partners on the delivery of an M&E training to DDR field practitioners.

NATO and DDRS collaboration on WAM

On 12 April, DDRS and ODA met with NATO to exchange on opportunities for collaboration on weapons and ammunition management, including through the joint DPO-ODA initiative on “Effective WAM in a Changing DDR Context”.

During the fruitful discussion, concrete entry-points for increased partnership were identified, including DDRS participation in the quarterly coordination meeting on Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) organized by NATO, as well as DDRS’s potential contribution to NATO’s web-portal on SALW projects and its annual training course on SALW. NATO and DDRS also agreed to stay closely in touch on potential country-specific projects and assistance on WAM in NATO’s focus regions, including MENA and the Sahel.

Group of Friends of DDR meeting

With the secretariat support provided by DDRS, Cote d’Ivoire and Egypt co-chaired on the 12th of February 2021 an expert-level meeting of the Group of Friends of DDR on the political situation and DDR processes in the Central African Republic and Mali.

The Group was briefed by Deputies SRSG from MINUSCA and MINUSMA who provided a comprehensive overview of recent political developments and the respective Heads of DDR components who briefed members of the Group on the achievements and challenges associated with advancing integrated DDR processes.

African Union (AU) – DDR Capacity Programme 2021

DDRS met with the World Bank (WB), the United Nations Office to the African Union (UNAOU), and the AU counterparts as part of the AU DDR Capacity Programme (AUDDRCP), to set the agenda for 2021.

Within the AUDDRCP, initiated in 2012, DPO, the World Bank and the UNOAU provide technical assistance to Member States, including GoDRC, Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and Peace Support Operations (PSOs) in designing and implementing DDR processes. The third phase of the program (covering 2019-2021), seeks to (i) streamline DDR in the overall political and conflict resolution processes across the continent; (ii) reinforce operational response through urgent technical and capacity support to Member States and PSOs; and (iii) foster institutional capacity building, knowledge management and cross-institutional learning in line with the national and regional policy frameworks, including the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) framework as well as the Silencing of the Guns in Africa.

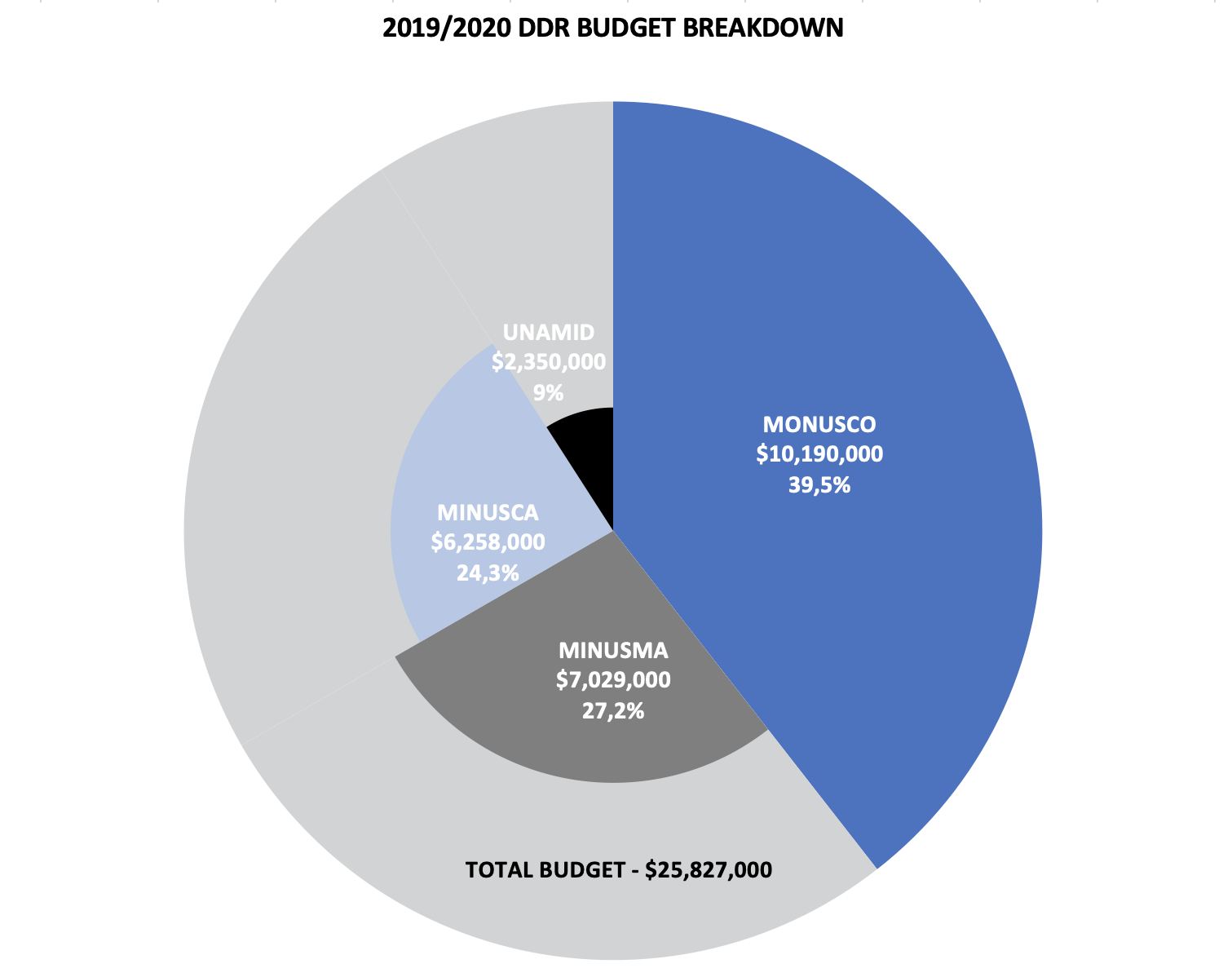

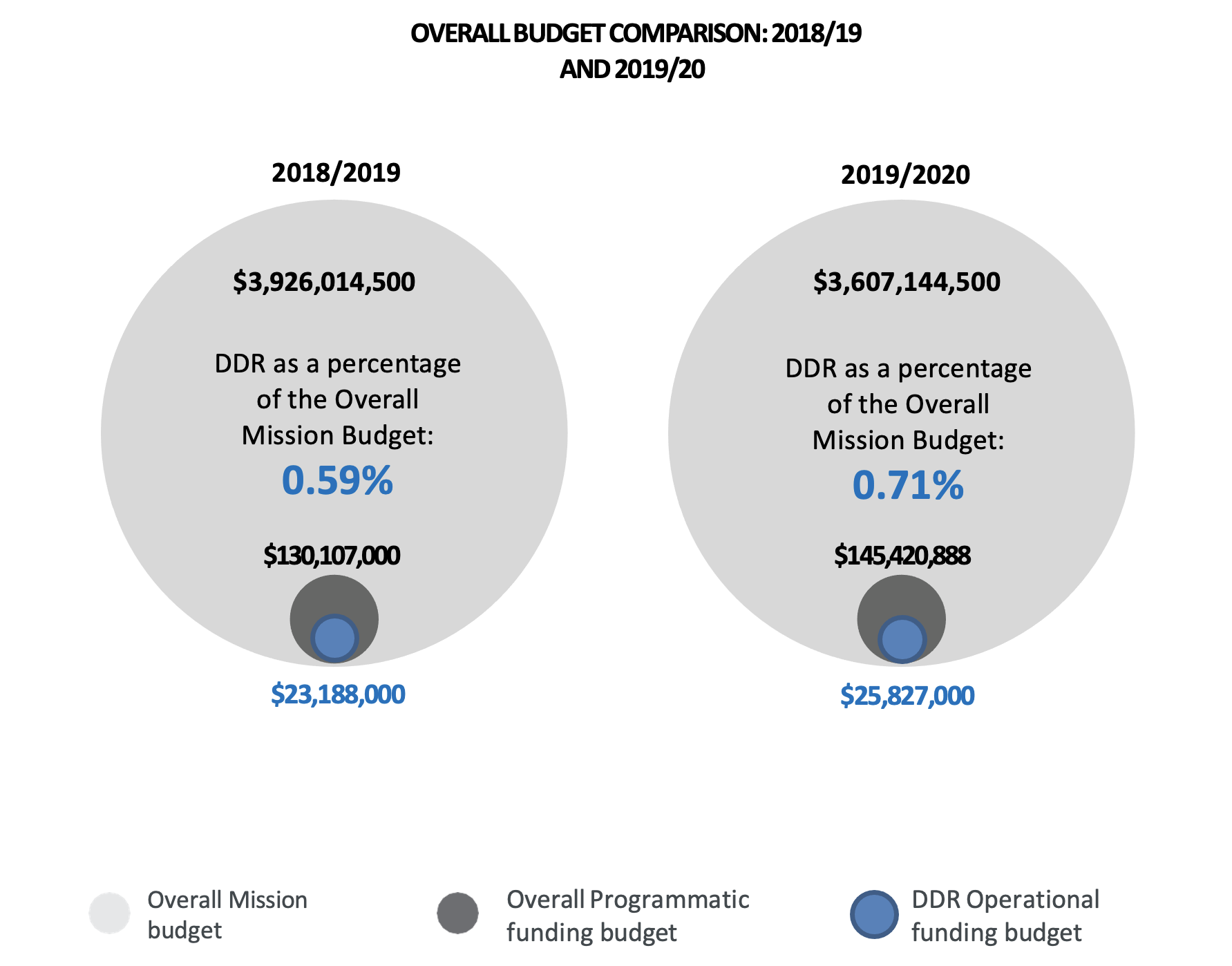

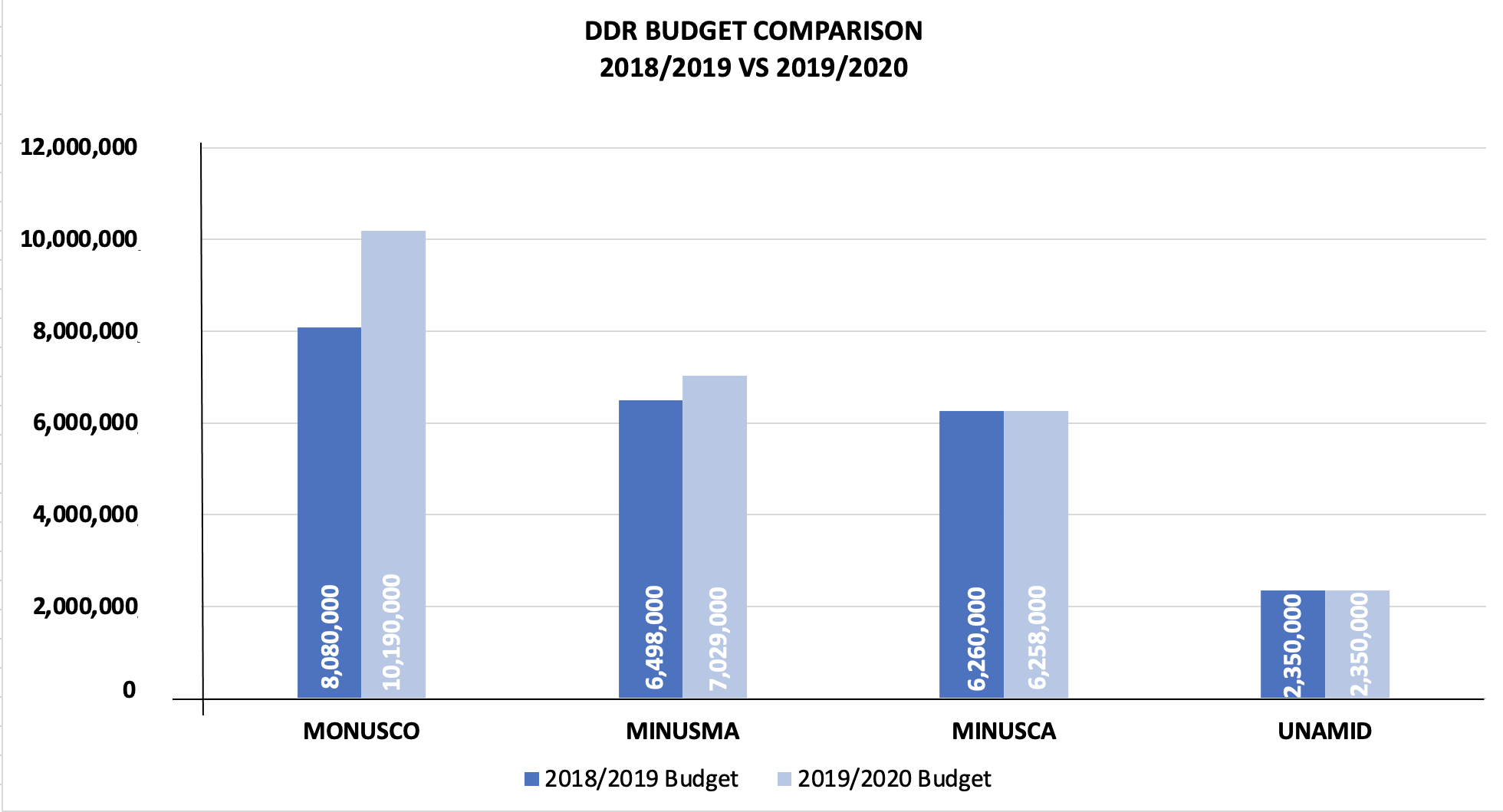

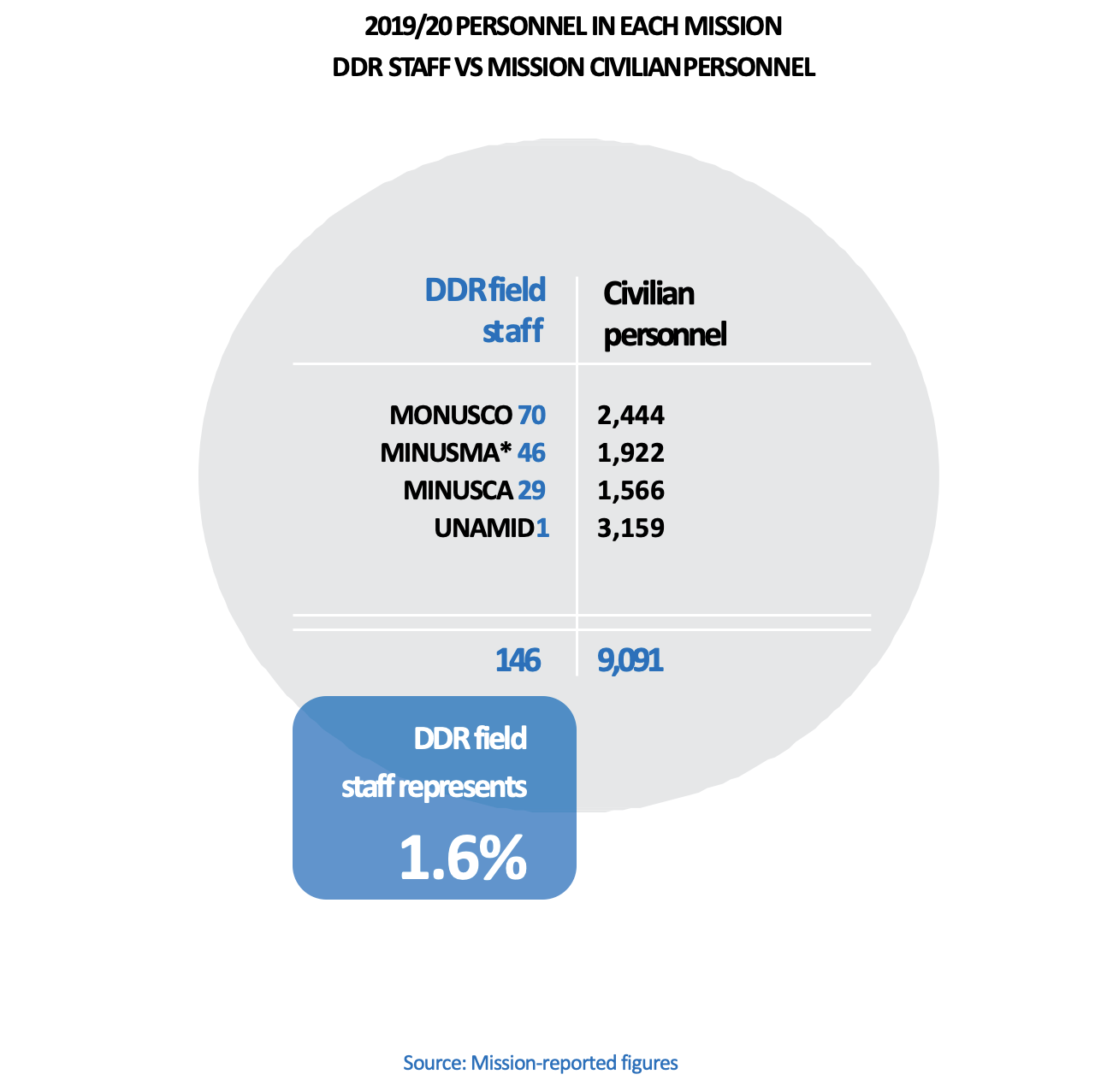

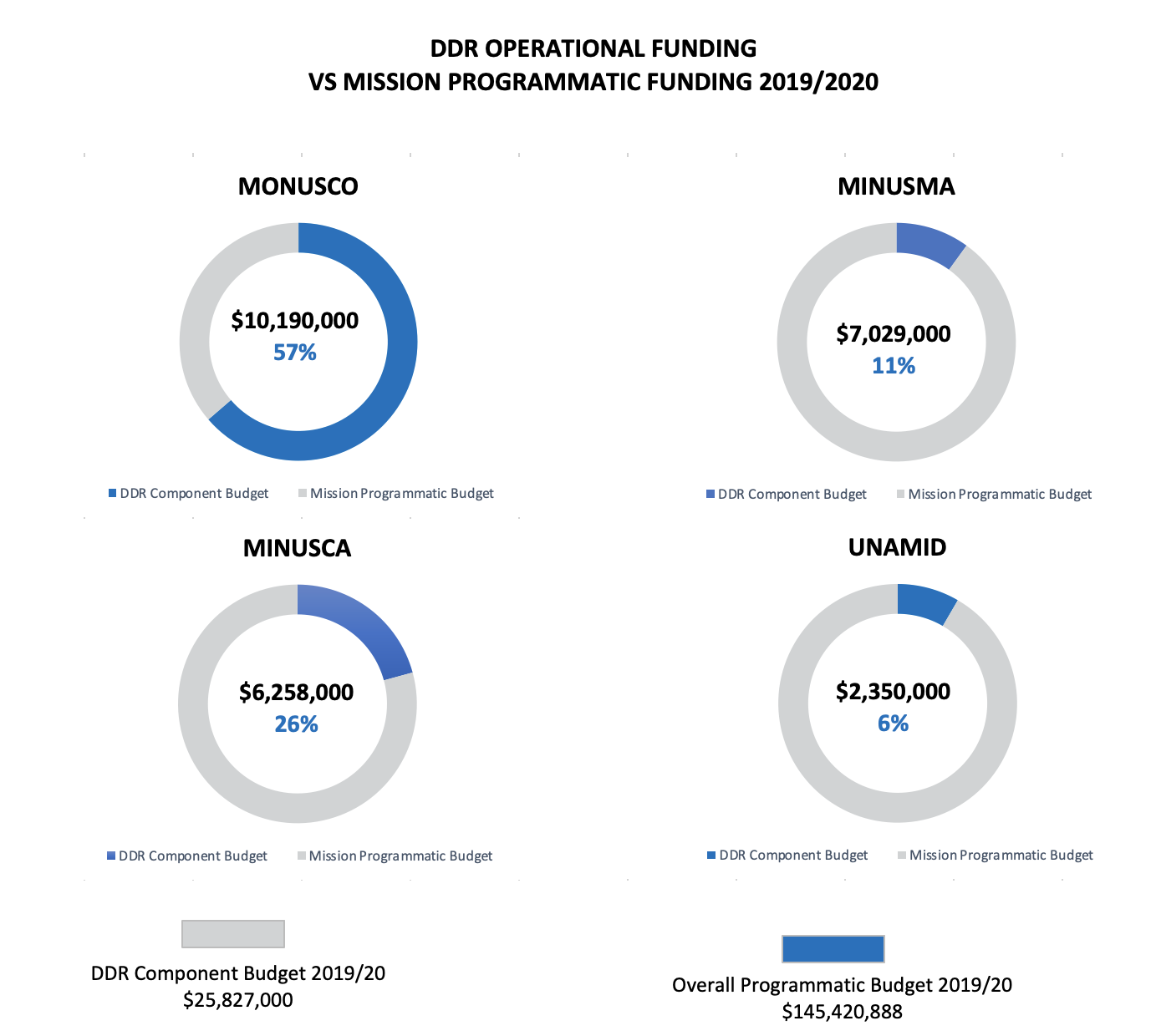

programmatic funding

TESTIMONIals From the Field

Jean-Marc Tafani

Head of the disarmament process for the U.N. peacekeeping mission in the Central Africa Republic, MINUSCA.

EN FR

Why DDR? How did your previous career lead you to becoming a DDR practitioner and eventually DDR Chief?

I stumbled onto DDR by chance in 2003. I was in the army and deployed for one year to MONUC to the post of deputy director of the DDRRR Section. Back then, MONUSCO was focused above all on the repatriation of the FDLR elements to Rwanda and the director put me in charge of the other components of the nascent DDR. I participated alongside the representatives of the Congolese authorities and the World Bank in the development of the DDR plan for the DRC. A year later, I left the army and joined the World Bank as a consultant to support the implementation of the programme. I learned a lot about DDR during this time and, above all, it allowed me to establish lasting attachments. After that, I moved to the Côte d’Ivoire, DRC again where I replaced my good Friend Gromo [*Gregory Alex, a long term MONUC/MONUSCO DDR Chief who passed away in 2013] upon his passing and finally to the Central African Republic. I stayed with DDR for fifteen years.

I stumbled onto DDR by chance in 2003. I was in the army and deployed for one year to MONUC to the post of deputy director of the DDRRR Section. Back then, MONUSCO was focused above all on the repatriation of the FDLR elements to Rwanda and the director put me in charge of the other components of the nascent DDR. I participated alongside the representatives of the Congolese authorities and the World Bank in the development of the DDR plan for the DRC. A year later, I left the army and joined the World Bank as a consultant to support the implementation of the programme. I learned a lot about DDR during this time and, above all, it allowed me to establish lasting attachments. After that, I moved to the Côte d’Ivoire, DRC again where I replaced my good Friend Gromo [*Gregory Alex, a long term MONUC/MONUSCO DDR Chief who passed away in 2013] upon his passing and finally to the Central African Republic. I stayed with DDR for fifteen years.

Je suis tombé dans le DDR par hasard en 2003. J’étais militaire détaché pour un an à la Monuc au poste d’adjoint du directeur de la section DDRRR. A cette époque la MONUSCO était surtout préoccupée par le rapatriement des FDLR au Rwanda. Le directeur m’avait laissé la partie DDR naissante. J’ai participé avec les responsables congolais et la Banque mondiale à l’élaboration du plan DDR de la RDC. Un an plus tard je quittais l’armée et je rejoignais la WB comme consultant pour la mise en œuvre du programme. J’ai beaucoup appris sur le DDR pendant cette période et surtout j’y ai noué des liens solides. Je suis ensuite passé par la Côte d’Ivoire, la Monusco encore où j’ai remplacé mon ami Gromo après son décès et enfin la RCA. Je suis resté DDR pendant quinze ans.

Je suis tombé dans le DDR par hasard en 2003. J’étais militaire détaché pour un an à la Monuc au poste d’adjoint du directeur de la section DDRRR. A cette époque la MONUSCO était surtout préoccupée par le rapatriement des FDLR au Rwanda. Le directeur m’avait laissé la partie DDR naissante. J’ai participé avec les responsables congolais et la Banque mondiale à l’élaboration du plan DDR de la RDC. Un an plus tard je quittais l’armée et je rejoignais la WB comme consultant pour la mise en œuvre du programme. J’ai beaucoup appris sur le DDR pendant cette période et surtout j’y ai noué des liens solides. Je suis ensuite passé par la Côte d’Ivoire, la Monusco encore où j’ai remplacé mon ami Gromo après son décès et enfin la RCA. Je suis resté DDR pendant quinze ans.

As a Chief of Section, what was a normal day like for you? What part of your work did you find the most satisfying?

There is no such thing as a “normal day” for a DDR Section Chief. Every single day is a new challenge. In theory, the mission seems very simple: disarm and reintegrate an armed group or another. But the implementation is much more complex and varies between countries: how to construct camps for hundreds of combatants in the middle of nowhere; what to do with their families; how to secure resources and how to utilize them; how to ensure the transportation for thousands of combatants; what to do with foreign deserters who want to return to their homelands; how to bring to the negotiation table a dozen of armed groups commanders who detest each other etc. etc. What is the most exciting is that one always ends up finding a solution!

There is no such thing as a “normal day” for a DDR Section Chief. Every single day is a new challenge. In theory, the mission seems very simple: disarm and reintegrate an armed group or another. But the implementation is much more complex and varies between countries: how to construct camps for hundreds of combatants in the middle of nowhere; what to do with their families; how to secure resources and how to utilize them; how to ensure the transportation for thousands of combatants; what to do with foreign deserters who want to return to their homelands; how to bring to the negotiation table a dozen of armed groups commanders who detest each other etc. etc. What is the most exciting is that one always ends up finding a solution!

Il n’y a pas de jour »normal » pour un chef de section DDR. Chaque jour est un challenge. En théorie la mission semble toujours simple, désarmer et réinsérer socialement tel groupe armé. La mise en œuvre est beaucoup plus complexe et différente dans chaque pays: comment monter des camps pour des centaines de combattant au milieu de nulle part, que faire de leurs familles, comment trouver des budgets et comment les utiliser, comment transporter des milliers de combattants, que faire de déserteurs étrangers qui veulent rentrer dans leur pays d’origine, comment amener à la table de négociation une douzaine de chefs de groupes armés qui se haïssent etc etc. Le plus exaltant c’est que l’on trouve toujours une solution.

Il n’y a pas de jour »normal » pour un chef de section DDR. Chaque jour est un challenge. En théorie la mission semble toujours simple, désarmer et réinsérer socialement tel groupe armé. La mise en œuvre est beaucoup plus complexe et différente dans chaque pays: comment monter des camps pour des centaines de combattant au milieu de nulle part, que faire de leurs familles, comment trouver des budgets et comment les utiliser, comment transporter des milliers de combattants, que faire de déserteurs étrangers qui veulent rentrer dans leur pays d’origine, comment amener à la table de négociation une douzaine de chefs de groupes armés qui se haïssent etc etc. Le plus exaltant c’est que l’on trouve toujours une solution.

What key challenges did you face as a DDR Chief?

I reckon all DDR Chiefs stand up to the same major challenges: to conceptualize a DDR plan both realistic and implementable; to maintain communications with armed groups and the trust of national authorities; to find adequate resources; to utilize the resources within a very strict set of the international rules and procedures; to procure the kits; to reintegrate the combatants in a country engulfed in a crisis, having extremely weak economic absorption capacities, to be capable of adjusting oneself to specific situations such as it was the case while working on CVR in the Central African Republic. And while attempting to face all of that, at all times, to have a plan B!

I reckon all DDR Chiefs stand up to the same major challenges: to conceptualize a DDR plan both realistic and implementable; to maintain communications with armed groups and the trust of national authorities; to find adequate resources; to utilize the resources within a very strict set of the international rules and procedures; to procure the kits; to reintegrate the combatants in a country engulfed in a crisis, having extremely weak economic absorption capacities, to be capable of adjusting oneself to specific situations such as it was the case while working on CVR in the Central African Republic. And while attempting to face all of that, at all times, to have a plan B!

Je pense que tous les chefs de section DDR font face aux mêmes challenges majeurs: concevoir un plan DDR réaliste et réalisable, le lien avec les groupes armés, la confiance des gouvernements, la recherche de budgets conséquents, l’utilisation de ces budgets suivants les règles internationales très strictes, les achats de kits, la réinsertion de combattants dans des pays en crise avec de très faibles capacités d’absorption économiques, la capacité de s’adapter à des situations particulières comme le CVR en RCA. Et surtout, avoir toujours un plan B!

Je pense que tous les chefs de section DDR font face aux mêmes challenges majeurs: concevoir un plan DDR réaliste et réalisable, le lien avec les groupes armés, la confiance des gouvernements, la recherche de budgets conséquents, l’utilisation de ces budgets suivants les règles internationales très strictes, les achats de kits, la réinsertion de combattants dans des pays en crise avec de très faibles capacités d’absorption économiques, la capacité de s’adapter à des situations particulières comme le CVR en RCA. Et surtout, avoir toujours un plan B!

What are you most proud of in DDR?

Before I get to what I am proud of, I must stress that oftentimes I witnessed with deep sadness failures and tragic human conditions. More often than not, it was due to the lack of will by the International Community to act. What brings some peace of mind is to think of those whom we did manage to help, of women and children we extracted from violence, all those we managed to send back home, of areas that we helped stabilize. What left its mark on me throughout those fifteen years are human relations, bonds of trust and mutual respect established with national partners, United Nations staff, international partners, such as the World Bank colleagues who placed their confidence in me and with the team in the UN Headquarters, always there to support and assist. I feel deep gratitude to all of them.

Before I get to what I am proud of, I must stress that oftentimes I witnessed with deep sadness failures and tragic human conditions. More often than not, it was due to the lack of will by the International Community to act. What brings some peace of mind is to think of those whom we did manage to help, of women and children we extracted from violence, all those we managed to send back home, of areas that we helped stabilize. What left its mark on me throughout those fifteen years are human relations, bonds of trust and mutual respect established with national partners, United Nations staff, international partners, such as the World Bank colleagues who placed their confidence in me and with the team in the UN Headquarters, always there to support and assist. I feel deep gratitude to all of them.

Technically, I am proud of our successes, and there were quite a few of those. One particular example, the establishment in the DRC of a joint operations center with the transportation team which helped us move and demobilize in one particular year more than 30,000 combatants. More recently, in the Central African Republic, the implementation of the Community Violence Reduction programmes – procurement and delivery of products to make this happen was an enormous challenge! I am so thankful to all those who contributed.

Avant d’être fier je suis triste de certains échecs ou de situations humaines tragiques, le plus souvent par manque de volonté de la Communauté internationale. Ce qui me tranquillise c’est de penser à tous ceux que l’on a pu aider, aux femmes et aux enfants que nous avons sortis de la violence,à ceux que nous avons pu reconduire chez eux, aux régions apaisées. Ce qui m’a beaucoup marqué pendant ces quinze années ce sont les rapports humains, les liens de confiance et de respect liés avec les partenaires nationaux, les staffs UN, les partenaires internationaux comme les collègues de la Banque mondiale qui m’ont fait confiance pendant toutes ces années et toute l’équipe de NYHQ toujours prête à nous soutenir et nous aider. J’en garde une profonde gratitude.

Avant d’être fier je suis triste de certains échecs ou de situations humaines tragiques, le plus souvent par manque de volonté de la Communauté internationale. Ce qui me tranquillise c’est de penser à tous ceux que l’on a pu aider, aux femmes et aux enfants que nous avons sortis de la violence,à ceux que nous avons pu reconduire chez eux, aux régions apaisées. Ce qui m’a beaucoup marqué pendant ces quinze années ce sont les rapports humains, les liens de confiance et de respect liés avec les partenaires nationaux, les staffs UN, les partenaires internationaux comme les collègues de la Banque mondiale qui m’ont fait confiance pendant toutes ces années et toute l’équipe de NYHQ toujours prête à nous soutenir et nous aider. J’en garde une profonde gratitude.

Techniquement je suis fier de nos réussites, nombreuses. Particulièrement la mise en œuvre d’un centre des opérations conjointes en RDC avec une équipe transport qui nous a permis de déplacer et de démobiliser en une année plus de 30 000 combattants. Plus récemment en RCA, le mise en œuvre de programmes de réduction de la violence communautaire, l’achat et le transport de marchandises pour ces plan a été un challenge énorme. Merci à tous ceux qui ont participé.

What is your perspective at the current evolution of Peacekeeping? Where do you think it is going? What is your opinion of Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) and its application in the field?

A difficult question. However, it seems to me that Peacekeeping is more and more absent from major zones of conflict. And this is not a good sign.

A difficult question. However, it seems to me that Peacekeeping is more and more absent from major zones of conflict. And this is not a good sign.

C’est une question très difficile. Cependant il semble que le peacekeeping soit actuellement absent des zones de crises majeures. Cela n’augure rien de bon.

C’est une question très difficile. Cependant il semble que le peacekeeping soit actuellement absent des zones de crises majeures. Cela n’augure rien de bon.

How has DDR changed throughout your career? Has there been a development of DDR? If yes, in what direction?

When I was beginning, DDR was really quite technical and prescriptive, with few variations from the template such as the repatriation of foreign combatants. As time went by, DDR has adapted to new missions and new theaters. It is in fact quite inspiring to see how innovative and stubborn DDR practitioners can be when it comes to implementing development and violence reduction programmes. Even more, so that Universities do not offer courses on how to do that. Fortunately, there are now some training courses offered by partners such as the Folke Bernadotte Academy in Sweden. Here, it is also important to recognize the emphasis that is nowadays being placed on the political aspect of DDR. From my very first deployment to the DRC, I have always felt very strongly that DDR is above all political and extremely sensitive.

When I was beginning, DDR was really quite technical and prescriptive, with few variations from the template such as the repatriation of foreign combatants. As time went by, DDR has adapted to new missions and new theaters. It is in fact quite inspiring to see how innovative and stubborn DDR practitioners can be when it comes to implementing development and violence reduction programmes. Even more, so that Universities do not offer courses on how to do that. Fortunately, there are now some training courses offered by partners such as the Folke Bernadotte Academy in Sweden. Here, it is also important to recognize the emphasis that is nowadays being placed on the political aspect of DDR. From my very first deployment to the DRC, I have always felt very strongly that DDR is above all political and extremely sensitive.

Quand j’ai commencé, le DDR était vraiment très technique et « réglementé « avec quelques variantes comme le rapatriement de combattants étrangers dans leur pays d’origine. Au fil du temps le DDR s’est adapté à de nouvelles missions et à de nouveaux théâtres. Il est d’ailleurs surprenant de voir combien les staffs DDR peuvent être inventifs et opiniâtres quand il s’agit de mettre en œuvre des programmes de développement et de réduction de la violence. D’autant plus qu’il n’existe pas réellement de cursus universitaire pour cette activité. Heureusement les différentes formations qui sont données comme par exemple par le FBA (Folke Bernadotte Academy). Ici, il faut bien reconnaitre l’importance qui est désormais attachée à l’aspect politique de DDR ; personnellement j’ai toujours eu le sentiment très fort, dès ma première mission en RDC , que le DDR était avant tout politique et extrêmement sensible.

Quand j’ai commencé, le DDR était vraiment très technique et « réglementé « avec quelques variantes comme le rapatriement de combattants étrangers dans leur pays d’origine. Au fil du temps le DDR s’est adapté à de nouvelles missions et à de nouveaux théâtres. Il est d’ailleurs surprenant de voir combien les staffs DDR peuvent être inventifs et opiniâtres quand il s’agit de mettre en œuvre des programmes de développement et de réduction de la violence. D’autant plus qu’il n’existe pas réellement de cursus universitaire pour cette activité. Heureusement les différentes formations qui sont données comme par exemple par le FBA (Folke Bernadotte Academy). Ici, il faut bien reconnaitre l’importance qui est désormais attachée à l’aspect politique de DDR ; personnellement j’ai toujours eu le sentiment très fort, dès ma première mission en RDC , que le DDR était avant tout politique et extrêmement sensible.

Looking back at your career what was the most impactful experience that changed you as a person?

As I already said, what left the most lasting imprint on me as a person, beyond programmatic successes, are human relations with all the people for whom or with whom I had a pleasure to work. The trust confided in me by combatants, partners, my supervisors have left a mark on my life. I think about them quite often.

As I already said, what left the most lasting imprint on me as a person, beyond programmatic successes, are human relations with all the people for whom or with whom I had a pleasure to work. The trust confided in me by combatants, partners, my supervisors have left a mark on my life. I think about them quite often.

Je l’ai déjà dit plus haut, ce qui m’a le plus touché en tant qu’homme au-delà de la réussite de certains programmes ce sont les relations humaines avec l’ensemble des personnes pour qui et avec qui j’ai travaillé. La confiance de combattants, de partenaires, de mes chefs m’ont beaucoup marqué. J’y pense très souvent.

Je l’ai déjà dit plus haut, ce qui m’a le plus touché en tant qu’homme au-delà de la réussite de certains programmes ce sont les relations humaines avec l’ensemble des personnes pour qui et avec qui j’ai travaillé. La confiance de combattants, de partenaires, de mes chefs m’ont beaucoup marqué. J’y pense très souvent.

In your belief, how will DDR evolve in the future? Where and into what should DDR evolve?

Another tough question. DDR will evolve hand in hand with Peacekeeping. But it will always need men and women capable of conceptualizing a realistic disarmament plan taking into a measured account the socio-economic implications of their actions. DDR is a potent tool but not a magic wand. The Heads of Missions who will know how to use it will be able to achieve through it a lot. But only on the condition that there will be sufficient will on the part of the International Community and resources adapted to tasks at hand.

Another tough question. DDR will evolve hand in hand with Peacekeeping. But it will always need men and women capable of conceptualizing a realistic disarmament plan taking into a measured account the socio-economic implications of their actions. DDR is a potent tool but not a magic wand. The Heads of Missions who will know how to use it will be able to achieve through it a lot. But only on the condition that there will be sufficient will on the part of the International Community and resources adapted to tasks at hand.

I have not served in areas affected by terrorism and don’t know related issues so I will abstain from giving opinions on those.

Development and violence reduction programmes are paths to follow but certainly not the only ones. I am confident that whatever the future has in store, the DDR practitioners will know how to adapt.

C’est encore une question difficile. Le DDR évoluera avec le peacekeeping. Mais il faudra toujours des hommes ou des femmes capables de concevoir un plan de désarmement réaliste mesurant toutes les conséquences sociales et économiques. Le DDR est un outil formidable, pas une baguette magique. Les chefs de mission qui sauront s’en servir pourront réaliser de grandes choses. A condition qu’il y ait une réelle volonté de la part de la Communauté internationale et des moyens adaptés aux missions données.

C’est encore une question difficile. Le DDR évoluera avec le peacekeeping. Mais il faudra toujours des hommes ou des femmes capables de concevoir un plan de désarmement réaliste mesurant toutes les conséquences sociales et économiques. Le DDR est un outil formidable, pas une baguette magique. Les chefs de mission qui sauront s’en servir pourront réaliser de grandes choses. A condition qu’il y ait une réelle volonté de la part de la Communauté internationale et des moyens adaptés aux missions données.

Je n’ai pas servi dans les zones touchées par le terrorisme. Je n’en connais pas bien les aspects alors j’évite de donner mon avis.

Les programmes de développement et de réduction de la violence sont des pistes mais certainement pas les seules. Je sais que les staffs DDR s’adapteront aux situations futures.

Sajeev WILL. ARA.

DDR Officer – UNOPS CAR

The interview with Sajeev WILL. ARA. aims at highlighting the significant role practitioners have and the challenges they face when working in the field. Specifically, Mr. Wijedasa answered questions related to his career in DDR and also provided his point of view on how DDR has evolved in the last decades.

Interview with Sajeev WILL. ARA.

IDDRS UPDATES

On 22 January, the final draft of the IDDRS module on DDR and Armed Groups Designated as Terrorist Organizations (AGDTO) was submitted for validation to the UN entities members of the Inter-Agency Working Group (IAWG) on DDR. The dissemination of the module constitutes a critical milestone, as it represents the final step prior to its official adoption. Over 2 years have passed since the inception of the operational guidance, which responded to the demands from DDR practitioners deployed in complex environments. Supported by the European Union, the module required extensive consultations among IAWG entities in order to harmonize perspectives and consolidate institutional buy-in.

Also as part of the IDDRS revision process, the DDRS hosted a dedicated webinar on the latest draft of IDDRS module 6.30 on DDR and Natural Resources, bringing together IAWG members as well as private sector entities working in the field of supply chain tracing and natural resource due diligence. This module provides DDR policy makers and practitioners – in mission and non-mission settings – with necessary information on the linkages between natural resource management and integrated DDR processes during the various stages of the conflict-peace continuum, with particular emphasis on economic and social reintegration. The guidance highlights the role of natural resources in all phases of the conflict cycle, focusing especially on the linkages with armed groups, the war economy, and how natural resource management can be considered to support successful DDR processes. This module has now been shared for validation.

IDDRS 6.20 on DDR and Transitional Justice has been revised and a webinar to discuss this module was held on the 21 April. The module is now shared for validation.

Finally, three modules have been validated by the IAWG members since January: IDDRS 4.20 on Demobilization; IDDRS 4.60 on Public Information and Strategic Communication in Support of DDR; and IDDRS 6.40 on DDR and Organized Crime.

IDDRS Modules Status

modulex.xx

In Progress

modulex.xx

To Be Validated

modulex.xx

Completed

level 1

General IDDRS

module1.10

Introduction to the IDDRS

module1.10

Glossary: Terms and Definitions

level 2

Concepts, Policy and Strategy of the IDDRS

module2.10

The UN Approach to DDR

module2.11

The Legal Framework for UN DDR

module2.20

The Politics of DDR

module2.30

Community Violence Reduction

module2.40

Reintegration as Part of Sustaining Peace

level 3

Structures and Processes

module3.10

Integrated DDR Planning: Processes and Structures

module3.11

Integrated Assessments

module3.20

DDR Programme Design

module3.21

Participants, Beneficiaries, and Partners

module3.30

National Institutions for DDR

module3.40

Mission and Programme Support for DDR

module3.41

Finance and Budgeting

module3.42

Personnel and Staffing

module3.50

Monitoring and Evaluation

level 4

Operations, Programmes and Support

module4.10

Disarmament

module4.11

Transitional Weapons and Ammunition Management

module4.20

Demobilization

module4.30

Reintegration

module4.40

UN Military Roles and Responsibilities

module4.50

UN Police Roles and Responsibilities

module4.60

Public Information and Strategic Communication in Support of DDR

level 5

Cross-cutting Issues

module5.10

Women, Gender and DDR

module5.20

Children and DDR

module5.30

Youth and DDR

module5.40

Cross-border Population Movements

module5.50

Food Assistance in DDR

module5.60

HIV/AIDS and DDR

module5.70

Health and DDR

module5.80

Disabilities and DDR

level 6

Linkages

module6.10

DDR and SSR

module6.20

DDR and Transitional Justice

module6.30

DDR and Natural Resources

module6.40

DDR and Organized Crime

module6.50

DDR and Armed Groups Designated as Terrorist Organisations

Upcoming

Events

Brownbag discussion with the Institute for Security Studies (ISS)

Agenda: Managing the journey out of violent extremism in the Lake Chad Basin

Date: 04 May, 2021

Time: 10 am (NY time)

Brownbag discussion with Mary Beth Altier (author)

Agenda: Violent Extremist Disengagement & Reintegration – Lessons from Over 20 Years of DDR

Date: 14 May, 2021

Time: 10 am (NY time)

Joint UN-ZIF Berlin Expert Dialogue

Agenda: Challenges in Peace Operations related to Armed Groups Designated as Terrorist Organizations

Date:14-15 June, 2021

High Level Launch Event of the joint DPO/BICC Study on The Future of DDR

Agenda: High-level discussion on the Study, and launching of the Virtual DDR Senior Officers Symposium

Date: 22 June, 2021

Training Opportunities

The recently updated Compendium of DDR Training Courses provides an overview of training opportunities provided by the United Nations System, by partner organizations, and training institutes. Upcoming opportunities include:

Foundational Training Course on DDR with Special Emphasis on Asymmetrical Contexts

Training provider: Cairo International Center for Conflict Resolution, Peacekeeping and Peacebuilding (CCCPA) and the Egyptian Agency for Partnership for Development (EAPD)

Format: Online

Date: 10 – 24 June 2021. Deadline for applications is 30 May 2021.

Link: https://www.cccpa-eg.org/disarmament

Effective Weapons and Ammunition Management in a Changing DDR context

Training provider: Department of Peace Operation (DPO) and Office of Disarmament Affairs (ODA)

Format: In person, Accra (Ghana)

Date: 13 -17 September 2021

Link: https://unddr-wam.org/